EPIC Letter to Attorney General Garland Re: ShotSpotter Title VI Compliance

Dear Attorney General Garland:

On behalf of the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), we write to you concerning the discriminatory impacts of automated decision-making and surveillance systems, particularly acoustic gunshot detection tools, funded in part by the Department of Justice and other federal agencies. Acoustic gunshot detection tools have disparate impacts on majority-minority neighborhoods, increasing police activity in neighborhood where sensors are placed, perpetuating patterns of policing practices.[1] Specifically, to comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), EPIC requests that you:

- Launch a compliance investigation about any funds granted by any agency or subagency within the DOJ that were used or permitted to be used to engage in contracts with SoundThinking (formerly known as ShotSpotter, Inc.) for its gunshot detection system, ShotSpotter;[2]

- Pause all DOJ financial assistance for the purchase and use of ShotSpotter unless and until the DOJ ascertains whether such assistance complies with Title VI;

- Publish a report with the findings of that investigation along with an inventory of all ShotSpotter purchases made with DOJ financial assistance;

- Issue—and make public—legal and policy guidance on the application of Title VI to ShotSpotter and other automated surveillance systems, including specific guidance on standards and procedures for conducting compliance review of these systems;

- Improve guidelines and standards for the development of consistent and effective recordkeeping of grants and the downstream use of awarded funds;

- Establish rules to ensure that federal financial assistance that is used on automated decision-making systems is transparent, accountable, and nondiscriminatory in line with established government guidance on the use of automated technologies;[3] and

- Bolster cooperation between all grantmaking agencies to ensure procurement of automated decision-making and surveillance systems meets minimum standards of non-discrimination, and that adoption of these systems is justified and necessary to achieve a defined goal.

ShotSpotter is just one of the many automated decision-making and surveillance systems procured or developed with federal funds that have a racially discriminatory impact. EPIC urges you to assess Title VI compliance of both past and current funding streams for systems used by the law enforcement and within the criminal justice system.

Title VI

Title VI prohibits recipients of federal financial assistance from discriminating based on race, color, and national origin.[4] Title VI’s prohibition “applies to intentional discrimination as well as to procedures, criteria or methods of administration that appear neutral but have a discriminatory effect on individuals because of their race, color, or national origin.”[5] Title VI may be violated where “a predominantly minority community is provided lower benefits, fewer services, or is subject to harsher rules than a predominantly nonminority community.”[6] It also may be violated where a recipient of federal financial assistance relies on biased assumptions about certain individuals and groups to determine how and when to apply particular procedures or methods.[7]

Title VI empowers federal agencies that disburse financial assistance to ensure discrimination does not occur “by issuing rules, regulations, or orders” consistent with the objective of Title VI.[8] To implement these regulations, agencies must undertake periodic compliance investigations, as well as launch a prompt investigation “whenever a compliance review, report, complaint, or any other information indicates a possible failure to comply with” Title VI obligations.[9]

To facilitate compliance efforts, Title VI also imposes affirmative obligations on recipients of federal financial assistance. Recipients must submit assurances, maintain compliance reports, monitor sub-recipients, and permit agencies to access their “books, records, accounts and other sources of information, and . . . [their] facilities as may be necessary, to ascertain compliance with federal civil rights requirements.”[10]

If voluntary compliance is unattainable, funding agencies are authorized to terminate or reject applications for federal financial assistance.[11] Agencies may also pursue court enforcement or administrative action to ensure compliance with Title VI.[12]

In addition to its obligation to ensure its own financial assistance is compliant with Title VI, the DOJ also coordinates between agencies. Under its regulation implementing Title VI, the DOJ may:

- Review existing and proposed rules, regulations, and orders of general applicability of the Executive agencies to identify those that are inadequate, unclear, or unnecessarily inconsistent;

- Develop specific standards and procedures for taking enforcement actions and for conducting investigations and compliance reviews;

- Issue guidelines for establishing reasonable time limits on efforts to secure voluntary compliance, on the initiation of sanctions, and for referral to DOJ of enforcement where there is noncompliance;

- Establish and implement a schedule for the review of the agencies’ regulations that implement Title VI and related statutes;

- Establish guidelines and standards for the development of consistent and effective recordkeeping and reporting requirements for Executive agencies; for the sharing and exchange of agency compliance records, findings, and supporting documentation; for the development of comprehensive employee training programs; and for the development of cooperative programs with state and local agencies, including sharing of information, deferring of enforcement activities, and providing technical assistance;

- Initiate cooperative programs between and among agencies, including the development of sample memoranda of understanding, designed to improve the coordination of Title VI and related statutes.[13]

Thus, the DOJ plays a key role in ensuring “the consistent and effective implementation of Title VI across the federal government.”[14]

However, despite evidence of discriminatory harm, law enforcement agencies continue to funnel federal money into more automated decision-making and surveillance systems, with no public indication that they have rigorously assessed their compliance with Title VI obligations. As EPIC has noted previously to the DOJ in the context of predictive policing tools, algorithms used in law enforcement contexts can disproportionately harm people of color if they are built on “dirty data” that recreates historically biased law enforcement practices.[15] Many algorithms are “prone to overstating the likelihood of crime occurring among poor and minority populations that are already overpoliced.”[16] Public evidence indicates that ShotSpotter’s system, deployment, and use raise many of these same concerns, making it a ripe area for a Title VI compliance investigation.

ShotSpotter

While ShotSpotter is only one of myriad automated decision-making systems used by law enforcement, substantial evidence—including multiple Inspector General investigations, other studies, and lawsuits against the company—indicates that the federally funded use of ShotSpotter has a discriminatory impact based on race.

ShotSpotter operates based on a network of acoustic sensors placed on top of buildings or light poles throughout designated areas, which listen for loud, impulsive sounds that might be gunfire and capture the time and audio associated with that sound.[17] ShotSpotter then filters those sounds through algorithms designed to classify the event, relaying potential gunshots to ShotSpotter personnel for review.[18] These personnel then share alerts of suspected gunshots with law enforcement.[19]

State and local police departments around the country have used federal financial assistance to facilitate the purchase of a slew of surveillance and automated decision-making technologies, including ShotSpotter. Based on publicly available information, the DOJ has awarded over $57 million in grants to local police departments through Smart Policing Programs.[20] Since 2021, the DOJ has granted $3,943,002 to police departments to improve “data-driven” policing, “smart” policing, and related practices.[21] The federal government has also awarded other grants to at least ten local governments, totaling at least $3.9 million in funds for ShotSpotter deployment.[22] These awards are typically block grants under the DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs (OJP) Bureau of Justice Assistance. Along with these OJP funds, SoundThinking has benefited from federal financial assistance via the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).[23]

Despite the relatively high profile of ShotSpotter—and substantial evidence of its discriminatory impact—there is no public indication that these recipients of federal funding have conducted a rigorous Title VI compliance investigation. Nor is there any indication that the federal agencies providing that financial assistance have conducted their own investigations, as required when information indicates potential Title VI noncompliance.[24] The diverse sources of financial assistance used to purchase ShotSpotter create more urgency for government agencies to investigate potential noncompliance with Title VI. The DOJ must also catalogue and publish information about federally funded purchases of ShotSpotter and other automated decision-making and surveillance systems to ensure that federal agencies’ application of Title VI to these tools is effective and consistent.

- Substantial evidence indicates that ShotSpotter is used in a biased and discriminatory manner, possibly violating Title VI.

Local police departments continue to purchase trials of ShotSpotter despite substantial evidence that the system is inaccurate, producing tens of thousands of false alerts of gun-related crime with little evidence that it improves public safety. There is also substantial evidence suggesting that ShotSpotter disproportionately deploys its sensors in predominantly Black neighborhoods, replicating biased policing practices by relying on historical crime data. Finally, studies have reported that the mere presence of ShotSpotter sensors in a particular neighborhood primes police to respond to a location with the expectation of a violent encounter, raising the risk of serious harm to community members. Together, this substantial evidence indicates that recipients’ use of federal financial assistance to fund ShotSpotter deployment may violate Title VI.

- Studies have indicated that ShotSpotter’s acoustic detection system produces tens of thousands of false alerts of gun-related crime.

ShotSpotter’s acoustic detection systems are known to provide false alerts due to a number of factors, including the density of the urban neighborhoods in which they operate, as well as the frequency of other impulsive sounds like fireworks.[25] These false alerts prompt frequent police responses in these predominantly Black neighborhoods.[26]

In 2021, the Inspector General of Chicago conducted the most revealing and public evaluation of ShotSpotter’s effectiveness, painting a damning picture of the tool’s impact in light of its significant cost—$33 million for only three years of service.[27] Over 17 months in that period, the Chicago IG reported that over 50,176 ShotSpotter alerts were “confirmed as probable gunshots by ShotSpotter,” each of which resulted in a police response to the alerted area.[28] Only 9.1% of those led to police finding any evidence related to a gun-related crime.[29]

Publicly available data from other cities has only furthered questions about ShotSpotter’s effectiveness. In Houston, more than 80% of ShotSpotter’s 6,300 reports between December 2020 and March 2023 were cancelled, marked as unfounded, dismissed, or closed because officers did not find evidence upon arrival.[30] In Dayton, only 118 of the 2,215 ShotSpotter alerts sent between December 11, 2020, and June 30, 2021, resulted in police reporting an incident with any crime;[31] the Dayton Police Department announced in late 2022 that it would not renew its contract with ShotSpotter, due in part to the challenge of developing statistics establishing ShotSpotter’s efficacy.[32] Dayton is one of a number of municipalities that has either cancelled its contract or chosen to not renew or extend its contract due at least in part to concerns that the frequency of false ShotSpotter alerts wasted critical law enforcement resources.[33]

The challenge in conclusively establishing ShotSpotter’s efficacy—as well as its potential for discriminatory impact—is due in part to the opacity of ShotSpotter’s algorithmic system and SoundThinking’s continued resistance to transparency. As with other algorithmic systems, it is difficult to precisely and definitively determine how ShotSpotter’s algorithms process and classify the sound recorded on public streets as a gunshot. This lack of understanding exists not because of technical complexity, but because SoundThinking has previously resisted disclosing this information—even in judicial proceedings—because of concerns that such disclosure may harm the company’s profits.[34] Such resistance to transparency makes it even more difficult for courts, the public, and regulators to assess the effectiveness—and the potential to produce discriminatory effects—of tools like ShotSpotter.[35] This intentional opacity may also run afoul of affirmative obligations to provide access to information relating to compliance with Title VI.[36]

While SoundThinking has disputed these critical studies and commissioned several of its own based on internal data,[37] agencies are nonetheless obligated under their own implementing regulations to investigate whether purchase and use of ShotSpotter is consistent with Title VI. These regulations require agency investigations whenever there is “information indicat[ing] a possible failure to comply” with Title VI, not only when there is definitive proof.[38] These studies—based on what public data is available—provide substantial evidence indicating that ShotSpotter exacerbates discriminatory policing patterns without leading to significant related evidence. Therefore, federally funded purchases of ShotSpotter are ripe for Title VI investigation, notwithstanding SoundThinking’s objections.

- ShotSpotter relies on biased assumptions and historical crime data to determine placement of its sensors, concentrating them in predominantly Black neighborhoods.

As government agencies—including the DOJ—have underscored, automated systems may contribute to unlawful discrimination if their outcomes are skewed by “unrepresentative or imbalanced datasets, datasets that incorporate historical bias, or datasets that contain other types of errors.”[39] This appears particularly true of ShotSpotter.

According to SoundThinking and a SoundThinking-commissioned report, SoundThinking “[uses] a data-driven approach” and cooperation with clients to determine the geographic areas for ShotSpotter deployment “(i.e.[,] the most gun violent areas)” based on “incidents of homicide and gun crime.”[40]

However, while ShotSpotter and law enforcement partners often publish the general locations that sensors may be deployed, the precise locations of deployed ShotSpotter sensors are largely secret.[41] When the Chicago OIG undertook its study of ShotSpotter, it was not provided access to ShotSpotter data about precise sensor locations, emblematic of the larger opacity issues with ShotSpotter’s systems. Therefore, the Chicago OIG report—and the other public reports on ShotSpotter’s disparate impact—have had to rely on the number of ShotSpotter dispatches per police district as a proxy for sensor placement.[42]

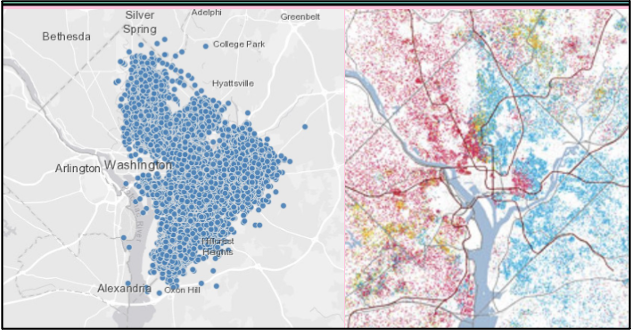

Even relying on ShotSpotter dispatches as a proxy for sensor location, it appears that in practice, ShotSpotter sensors are placed almost exclusively in communities of color.[43] The maps below demonstrate that in Chicago, ShotSpotter sensors and “hits” of “probable” gunshots are heavily concentrated in Black neighborhoods, whereas neighborhoods with more White people were either “not confirmed to have ShotSpotter sensors” at all or had 0-1 sensors.

In Chicago, ShotSpotter sensors have been deployed only on the city’s south and west sides, concentrated in the twelve police districts that are primarily made up of Black and Latinx residents.[44] ShotSpotter’s sensors cover 80% of Chicago’s Black residents, 65% of Chicago’s Latinx residents, and only 30% of Chicago’s white residents.[45]

Figure 1. Comparison of ShotSpotter Sensor Placement and

Demographic Breakdown of Chicago Police Districts

(Source: MacArthur Justice Center)[46]

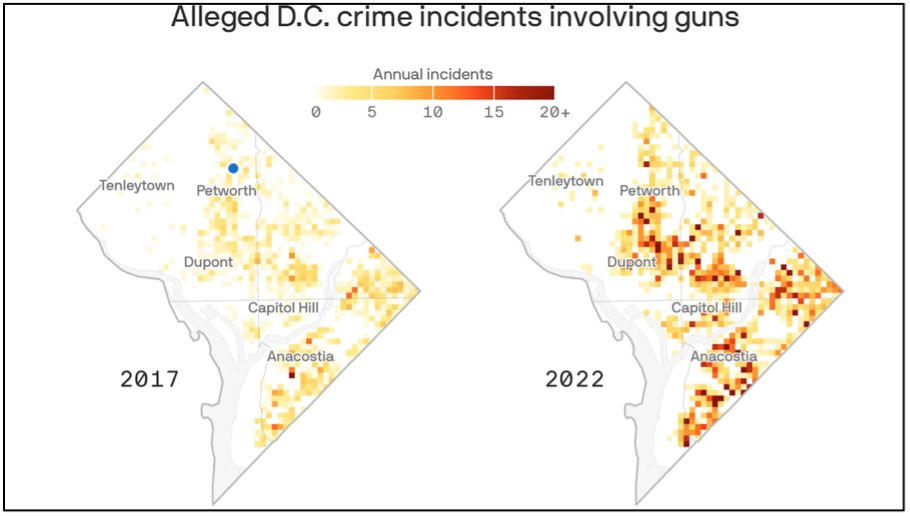

Similarly, in Washington, D.C., although there is no transparency about where sensors are placed, there are no “hits” of gunshots recorded in neighborhoods west of Rock Creek Park, which are predominantly white. Of course, this is not because of a lack of gunshots in the area over the last ten years that MPD has contracted with ShotSpotter/SoundThinking.[47]

Figure 2. Alleged D.C. Crime Incidents Involving Guns

(Source: Axios)

Figure 3. Comparison of ShotSpotter Placement (left) and Racial Demographics Map of Washington, D.C. (right). On the demographics map, red dots represent 25 white residents and blue dots represent 25 black residents.

(Sources: Shotspotter – DC Open Data; Demographics map, Greater Greater Washington)

Other examples of the disparate placement of these systems include:

- In Houston, people of color made up 95% and 80% of the population in the two ShotSpotter pilot program zones.[48]

- In Dayton, Ohio, ShotSpotter’s first deployment was in west Dayton, “the heart of the city’s Black community.”[49]

- In Kansas City, Missouri, ShotSpotter was deployed in a 3.5-square-mile area of the city in neighborhoods where White people make up only 3.5% of the population.[50]

- Newark expanded its use of ShotSpotter into schools in 2021, and 30 of the 34 school buildings selected are in majority Black zip codes in schools with nearly 70% Black students.[51]

While SoundThinking justifies these disparities based on historic crime data, its continued reliance on this “dirty data” recreates historically biased law enforcement practices and provides nominally data-driven support to continue overpolicing.[52] These tools rely on historical crime data to determine future resource allocation, such as the placement of sensors. It is well-documented that certain crimes may be under-reported, causing algorithms understate the likelihood of crime occurring in less-policed neighborhoods.[53] Therefore, these algorithms are prone to overstating the likelihood of crime occurring among poor and minority populations that are already overpoliced.[54] By relying on historical crime data, systems like ShotSpotter are also vulnerable to “juked stats,” the result of law enforcement agencies deliberately discouraging reporting in certain locations to appear more effective.[55]

In addition to relying on “dirty data” inputs as their foundation, ShotSpotter and other automated decision-making and surveillance systems also create a “dirty data” feedback loop. By selectively placing sensors in those neighborhoods highlighted in historical crime data, these tools “bake in” and recreate trends in overpolicing, prompting further police interventions in these areas. These more frequent police interventions may lead to arrests, citations, or other infractions—whether related to the initial gunshot alert or not.[56] These interventions only increase crime statistics, which are subsequently factored back into these systems. ShotSpotter’s reliance on historical gun crime and homicide data to determine sensor placement illustrates the harms caused by this cycle.

- The introduction of ShotSpotter has caused further overpolicing of predominantly Black neighborhoods because alerts prime police to engage with force, and the mere presence of historical ShotSpotter alerts leads to increased police activity in predominantly Black communities.

Studies of ShotSpotter have revealed that ShotSpotter primes police to anticipate arriving at a dangerous situation when responding to alerts, increasing the likelihood that responding officers will use force. Because ShotSpotter’s alerts detail possible gunfire, officers arrive at the location detailed in the ShotSpotter alert already believing—correctly or not—that individuals at the scene may be armed and dangerous.

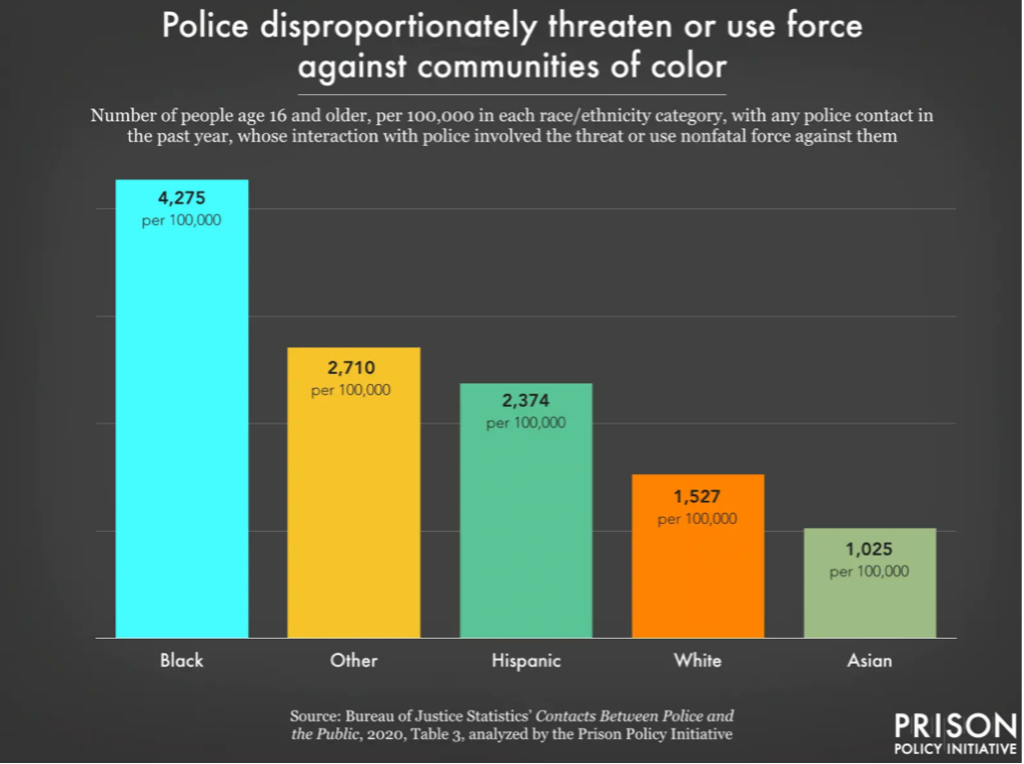

A survey conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics illustrated that use of force against Black people is highest among any other demographic, and it is rising over time.[57] As detailed in the chart below—based on analysis of that survey—Black individuals had nearly three times the number of interactions with police that involved the threat or use of force.[58] These findings are consistent with other studies that have shown that police officers stop and search Black individuals at rates far higher than other groups, and that although police rarely use force during stops, “they are more like to use force when they stop African Americans, even when the stop does not begin because police believe that a crime is in progress.”[59]

Figure 4. Analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Contacts Between

Police and the Public

(Source: Prison Policy Initiative)

The use of ShotSpotter exacerbates this problem. The Chicago OIG report also concluded that the mere introduction of ShotSpotter “changed the way some [police officers] perceive and interact with individuals present in areas where ShotSpotter alerts are frequent.”[60] According to the Chicago OIG report, police officers were more likely to be present and act aggressively because of the general frequency of ShotSpotter alerts in a given area—there were narratives from police officers showing they use the frequency of ShotSpotter alerts around an area as an element of reasonable suspicion for (1) a stop leading to arrest, (2) a stop, and (3) a pat-down.[61] Although the vast majority of these responses did not result in recovering evidence of a crime or a firearm, they resulted in thousands of pat-downs, searches, and unrelated arrests.[62] This changed behavior and increased police presence were felt mostly where the city confirmed there were ShotSpotter sensors, and primarily in majority Black neighborhoods.

As the ACLU puts it, “The placement of sensors in some neighborhoods but not others means that the police will detect more incidents (real or false) in places where the sensors are located. That can distort gunfire statistics and create a circular statistical justification for over-policing in communities of color.”[63] This will exacerbate an already troubling but clear trend: People of color are stopped and searched at higher rates than white people, and police officers are more likely to use force when a Black person is stopped, regardless of whether the stop began with suspicion of a crime.[64]

State and local police departments—using federal financial assistance—continue to pour money into ShotSpotter, despite the substantial body of public evidence that: (1) ShotSpotter’s gunshot detection system produces tens of thousands of false alerts of gun-related crime, leading to frequent police interventions with little to no public safety benefit; (2) SoundThinking disproportionately deploys ShotSpotter sensors in predominantly Black neighborhoods, replicating biased policing practices by relying on historical crime data; and (3) the mere presence of ShotSpotter sensors in a particular neighborhood primes police to respond to a location with the expectation of a violent encounter, raising the risk of serious harm to members of these predominantly Black communities. Given this substantial evidence of discriminatory impact, this use of federal financial assistance is ripe for Title VI investigation.

Requested Relief

R

In light of all the above, and pursuant to its Title VI authorities, EPIC urges the DOJ to:

- Launch a compliance investigation about any funds granted by any agency or subagency within the DOJ that were used or permitted to be used to engage in contracts with SoundThinking (formerly known as ShotSpotter, Inc.) for its gunshot detection system, ShotSpotter;

- Pause all DOJ financial assistance for the purchase and use of ShotSpotter unless and until the DOJ ascertains whether such assistance complies with Title VI;

- Publish a report with the findings of that investigation along with an inventory of all ShotSpotter purchases made with DOJ financial assistance;

- Issue—and make public—legal and policy guidance on the application of Title VI to ShotSpotter and other automated surveillance systems, including specific guidance on standards and procedures for conducting compliance review of these systems;

- Improve guidelines and standards for the development of consistent and effective recordkeeping of grants and the downstream use of awarded funds;

- Establish rules to ensure that federal financial assistance that is used on automated decision-making systems is transparent, accountable, and nondiscriminatory in line with established government guidance on the use of automated technologies; and

- Bolster cooperation between all grantmaking agencies to ensure procurement of automated decision-making and surveillance systems meets minimum standards of non-discrimination, and that adoption of these systems is justified and necessary to achieve a defined goal.

Please feel free to reach out to us at [email protected] and [email protected] for any questions or if you would like to work with EPIC in applying these recommendations.

[1] See infra Part II.A.

[2] See Dell Cameron, Justice Department Admits: We Don’t Even Know How Many Predictive Policing Tools We’ve Funded, Gizmodo (Mar. 17, 2022), https://gizmodo.com/justice-department-kept-few-records-on-predictive-polic-1848660323 (detailing letter from the Department of Justice noting that it “[did] not have specific records” confirming the number of grantees under its Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Formula Program that use predictive policing).

[3] White House Off. of Sci. & Tech. Pol’y, Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights: Making Automated Systems Work for the American People (Oct. 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Blueprint-for-an-AI-Bill-of-Rights.pdf; AI Risk Management Framework Playbook, Nat’l Inst. of Standards & Tech. (Aug. 2022), https://pages.nist.gov/AIRMF/.

[4] 42 U.S.C. § 2000d.

[5] Civil Rights Requirements- A. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seq. (“Title VI”), U.S. Dep’t of Health & Hum. Servs., https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/special-topics/needy-families/civil-rights-requirements/index.html (last visited Sept. 15, 2023).

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-1.

[9] See 28 C.F.R. § 42.107 (DOJ implementing regulations) (emphasis added); 6 C.F.R. § 21.11(c) (DHS); 24 C.F.R. § 1.7 (HUD).

[10] See 28 C.F.R. §§ 105, 42.106(c) (DOJ); 6 C.F.R. §§ 21.7, 21.9(c) (DHS); 24 C.F.R. §§ 1.5, 1.6(c) (HUD).

[11] See 28 C.F.R. § 50.3.

[12] See id.

[13] 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-1.

[14] U.S. Dep’t of Just., Title VI Legal Manual 1, https://www.justice.gov/crt/book/file/1364106/download.

[15] Letter from EPIC to Attorney General Merrick Garland (July 6, 2022), https://epic.org/documents/epic-letter-to-attorney-general-garland-re-title-vi-compliance-and-predictive-algorithms/.

[16] Id. at 2.

[17] ShotSpotter, ShotSpotter Frequently Asked Questions 1 (Jan. 2018), https://www.shotspotter.com/system/content-uploads/SST_FAQ_January_2018.pdf.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Funding & Awards, Bureau of Just. Assistance (2023), https://bja.ojp.gov/funding.

[21] Funding & Awards, Bureau of Just. Assistance (2023), https://bja.ojp.gov/funding.

[22] See Spending by Prime Award, USASpending.gov, https://www.usaspending.gov/search/?hash=119556db9390fd744e86079d7001dbf6 (showing grants containing ShotSpotter in the award).

[23] See Emily Birnbaum, DHS Funds Surveillance Technology in US Cities, Report Says, Bloomberg (Dec. 6, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-12-06/dhs-funds-surveillance-technology-in-us-cities-report-says; Johana Bhuiyan, ‘Ready for Some Help?’: How a Controversial Technology Firm Courted Portland Police, Guardian (May 3, 2023), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/may/03/oregon-police-gunshot-detection-shotspotter; Vivekae M. Kim, Eyes and Ears in Cambridge, Harv. Crimson (Oct. 19, 2019), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2019/10/10/shot-spotter/.

[24] In response to an EPIC request to commission a study about biometric information and predictive algorithms in law enforcement, the DOJ Office of Justice Programs’ Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) emphasized that the DOJ “remains steadfastly committed to ensuring that policing practices are conducted in a fair and just manner that protects constitutional rights” and that “[c]oncerns regarding the nationwide impact of predictive policing on people in protected classes are at the forefront of BJA’s [training and technical assistance] engagements on these issues.” Letter from Karhlton F. Moore, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Off. of Just. Programs Bureau of Just. Assistance, to EPIC Executive Director Alan Butler (Nov. 16, 2022), https://epic.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/EPIC-EO14074-TitleVI-DOJ-Reply-Letter.pdf. However, BJA noted it did not have specific records of how many grantees use predictive policing tools, nor did it indicate that the DOJ had conducted compliance investigations to ensure that the use of such tools complied with Title VI. Id.

[25] City of Chi. Off. of the Inspector Gen., The Chicago Police Department’s Use of ShotSpotter Technology 4 (Aug. 24, 2021) [hereinafter Chicago OIG Report],

[26] See infra notes 43–55 and accompanying text.

[27] Id. at 2.

[28] Id. at 2–3.

[29] Id. at 3.

[30] Yilun Cheng, Houston’s Gunshot Alert System Isn’t Curbing Violence But Delays Police Response Times, Data Shows, Hous. Chron. (July 11, 2023), https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/investigations/article/houston-gun-alert-police-delays-18117579.php.

[31] Mawa Iqbal, ShotSpotter Generates Thousands of Alerts in Dayton, But Officers Find Few Crimes, WYSO (Oct. 4, 2021), https://www.wyso.org/local-and-statewide-news/2021-10-04/shotspotter-generates-thousands-of-alerts-in-dayton-but-officers-find-few-crimes.

[32] Statement from the Dayton Police Department (Oct. 2022), https://www.daytonohio.gov/DocumentCenter/View/12880/ShotSpotter-Statement-PDF.

[33] SeeBrendan Max, SoundThinking’s Black-Box Gunshot Detection Method: Untested and Unvetted Tech Flourishes in the Criminal Justice System, 26 Stan. Tech. L. Rev. 193, 229–30 (2023), https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Publish_26-STLR-193-2023_SoundThinkings-Black-Box-Gunshot-Detection-Method.pdf (listing instances).

[34] See Matt Chapman & Jim Daley, ShotSpotter Held in Contempt of Court, Chicago Reader (July 26, 2022), https://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/shotspotter-held-in-contempt-of-court/; see also Max, supra note 33, at 238–39 (detailing how SoundThinking has sought to shield its protocols from disclosure).

[35] See Max, supra note 33, at 236–38 (noting how SoundThinking’s “incomplete approach to algorithm development, lack of peer-reviewed validation data, and complete absence of examiner error data” have “minimize[ed] opportunities for scientific and legal oversight” of its ShotSpotter systems); see also

Joint Statement on Enforcement Efforts Against Discrimination and Bias in Automated Systems (Apr. 25, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/EEOC-CRT-FTC-CFPB-AI-Joint-Statement%28final%29.pdf [hereinafter Joint Statement].

[36] See supra note 10 and accompanying text.

[37] SoundThinking has commissioned studies based on its own data, which the company says affirms its accuracy. See Edgeworth Analytics, Independent Audit of the ShotSpotter Accuracy, 2019-2022 (May 2, 2023), https://www.edgewortheconomics.com/assets/htmldocuments/Independent%20Audit%20of%20the%20ShotSpotter%20Accuracy%202019-2022.pdf.

[38] See 28 C.F.R. § 42.107 (DOJ implementing regulations) (emphasis added); 6 C.F.R. § 21.11(c) (DHS); 24 C.F.R. § 1.7 (HUD).

[39] Joint Statement, supra note 35, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/EEOC-CRT-FTC-CFPB-AI-Joint-Statement%28final%29.pdf (emphasis added).

[40] See SoundThinking, ShotSpotter Community Privacy Protections, https://www.soundthinking.com/privacy-policy/ (last updated Apr. 10, 2023); Edgeworth Analytics, Independent Analysis of the MacArthur Justice Center Study on ShotSpotter in Chicago 7 (July 22, 2021), https://www.edgewortheconomics.com/assets/htmldocuments/Shotspotter%20MJC%207-23%20Nov%202022.pdf. According to public records, the factors that go into final sensor location selection include: “[d]esired sensor density based on the unique geographical, topographical, and ambient acoustic features of the coverage area[;] [r]elative distance and spacing between other sensors; [h]eight of building or structure (to better “hear to the horizon” and thus minimize acoustic signal attenuation from far away gunfire); [a]vailability of reliable power; [a]dequate cellular coverage, signal strength and latency for communications; and [w]ritten permission from the property owner to install a sensor.” S.F. Police Dep’t, Surveillance Impact Report: Audio Recorder – ShotSpotter, Inc. (“ShotSpotter”) 5, available at https://sf.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/SFPD%20ShotSpotter%20Surveillance%20Impact%20Report.pdf.

[41] While SoundThinking asserts that it does not share the locations of its sensors with law enforcement partners as a matter of policy, it appears that at least in some jurisdictions, SoundThinking has engaged with law enforcement to place individual sensors. See Fola Akinnibi & Sarah Holder, In New York Neighborhood, Police and Tech Company Flout Privacy Policy, Advocates Say, Bloomberg (Dec. 5, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-12-15/nyc-police-and-tech-company-flout-privacy-policy-advocates-say.

[42] Per agency implementing regulations, recipients are required to provide the investigating agency access to “sources of information” and “its facilities” “as may be pertinent to ascertain compliance.” See 28 C.F.R. §§ 105, 42.106(c) (DOJ); 6 C.F.R. §§ 21.7, 21.9(c) (DHS); 24 C.F.R. §§ 1.5, 1.6(c) (HUD). These “facilities” include “all or any part” of structures or equipment. See, e.g., 6 C.F.R. §§ 21.4. Given these obligations, the DOJ and other agencies are best positioned to require recipients to provide the precise locations of its ShotSpotter sensors in order to comprehensively assess any discriminatory placement of sensors and ascertain compliance with Title VI. The DOJ or other agencies can also engage SoundThinking directly to provide these locations in order to avoid having SoundThinking disclose these precise locations to their local law enforcement partners, in violation of SoundThinking’s stated privacy policy.

[43] See Cheng, supra note 30; Helen Webley-Brown et al., ShotSpotter and the Misfires of Gunshot Technology 12 (July 14, 2022), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c1bfc7eee175995a4ceb638/t/62cc83c0118f7a1e018bf162/1657570241282/2022.7.7_ShotSpotter+Report_FINAL.pdf (reporting that ShotSpotter is deployed “almost exclusively” in communities of color in Cleveland, Atlanta, Kansas City, and New York City).

[44] Press Release, Class Action Lawsuit Takes Aim at Chicago’s Use of ShotSpotter After Unfounded Alerts Lead to Illegal Stops and False Charges, MacArthur Just. Ctr. (July 21, 2022), https://www.macarthurjustice.org/class-action-lawsuit-takes-aim-at-chicagos-use-of-shotspotter-after-unfounded-alerts-lead-to-illegal-stops-and-false-charges/.

[45] Id.

[46] Williams v. City of Chicago, MacArthur Just. Ctr., https://www.macarthurjustice.org/case/williams-v-city-of-chicago/.

[47] See, e.g., Cuneyt Dil, Washington Recovers After Violent Weekend, Axios (Apr. 25, 2022), https://www.axios.com/local/washington-dc/2022/04/25/washington-dc-weekend-shooting-van-ness; Shooting in Cleveland Park at 12:24am Last Night, Popville (Jan. 23, 2023), https://www.popville.com/2023/01/shooting-dc-cleveland-park/; Peter Hermann, Two Men Injured in Gunfire in Cleveland Park Neighborhood of Northwest Washington, Wash. Post (June 17, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/cleveland-park-shooting-washington/2021/06/17/831b531e-cf9c-11eb-8cd2-4e95230cfac2_story.html.

[48] Cheng, supra note 30.

[49] Stephen Starr, Why Dayton Quit ShotSpotter, a Surveillance Tool Many Cities Still Embrace, Bolts Mag. (July 13, 2023), https://boltsmag.org/dayton-shotspotter/.

[50] Todd Feathers, Gunshot-Detecting Tech Is Summoning Armed Police to Black Neighborhoods, Motherboard (July 19, 2021), https://www.vice.com/en/article/88nd3z/gunshot-detecting-tech-is-summoning-armed-police-to-black-neighborhoods.

[51] Patrick Wall, Newark Is Installing Gunshot Detectors on Mostly Black Schools as City Shootings Rise, Chalkbeat (July 26, 2021), https://newark.chalkbeat.org/2021/7/26/22594328/shotspotter-newark-schools.

[52] Rashida Richardson, Jason Schultz, & Kate Crawford, Dirty Data, Bad Predictions: How Civil Rights Violations Impact Police Data, Predictive Policing Systems, and Justice, 94 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 192–233 (2019), https://www.nyulawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/NYULawReview-94-Richardson-Schultz-Crawford.pdf.

[53] Annie Gilbertson, Data-Informed Predictive Policing Was Heralded as Less Biased. Is It?, The Markup (Aug. 20, 2020), https://themarkup.org/ask-the-markup/2020/08/20/does-predictive-police-technology-contribute-to-bias.

[54] Id.

[55] See Richardson, Schultz, & Crawford, supra note 52, at 193–198.

[56] Chicago OIG Report, supra note 25, at 24.

[57] Susannah N. Tapp & Elizabeth J. Davis, Contacts Between Police and the Public, 2020, Special Report, U.S. Dep’t of Just. (Nov. 2022), https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/cbpp20.pdf.

[58] Id.

[59] Nat’l Acads. of Sci., Eng’g & Med., Reducing Racial Inequality in Crime and Justice: Science, Practice and Policy 1 (2023), https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26705/reducing-racial-inequality-in-crime-and-justice-science-practice-and (“Police officers stop and search Black individuals at rates that are higher than for other racial and ethnic groups. . . . [T]he early stages of the system—including police stops, jail confinement, misdemeanor courts, and fines and fees—generate vast numbers of contacts (relative to White communities) between police and courts on the one hand and Black, Latino, and Native American communities on the other.”); id. at 66.

[60] Id. at 3.

[61] Id. at 20–21.

[62] Id. at 16.

[63] Jay Stanley, Four Problems with the ShotSpotter Gunshot Detection System, ACLU (Oct. 14, 2021), https://www.aclu.org/news/privacy-technology/four-problems-with-the-shotspotter-gunshot-detection-system+.

[64] See supra note 59.

News

EPIC Commends FTC’s GTL Data Breach Settlement, Urges Tailored Remedies

December 22, 2023

EPIC Commends FTC’s GTL Data Breach Settlement, Urges Tailored Remedies

December 22, 2023

Support Our Work

EPIC's work is funded by the support of individuals like you, who allow us to continue to protect privacy, open government, and democratic values in the information age.

Donate