ICE’s Privacy Impact Assessment on Surveillance Technologies is an Exercise in Disregarding Reality

October 5, 2023 |

A recent Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) published by the DHS in 2022 details ICE Homeland Security and Investigations’ use of several categories of surveillance technologies. The PIA outlines ICE’s narrow conception of a “reasonable expectation of privacy” that allows the agency to conduct broad surveillance without judicial oversight. Although the PIA describes a warrant requirement for certain surveillance activities, the assessment fails to address ICE’s ability to purchase the same data without a warrant from commercial entities. Additionally, the PIA ignores the deceptive tactics ICE has used to obtain consent for certain surveillance activities covered by this PIA. The shortcomings of the PIA are exacerbated by ICE’s history of abuse of its authority and the broad surveillance dragnet the agency has created, which leaves little doubt that ICE will not abide by the minimal requirements described in the PIA and guarantees that ICE will bypass warrant requirements by obtaining surveillance data from commercial entities.

Homeland Security Investigations

Homeland Security and Investigations (HSI) is a directorate under ICE and is the principal investigative component of the DHS. HSI has the “legal authority” to investigate, disrupt, and dismantle transnational crime. HSI’s legal mandate has come with a track record of questionable use of its authority.

HSI’s Abuse of Its Authority

Just this year, a review by the DHS Office of Inspector General determined that ICE HSI did not obtain necessary warrants when using cell-site simulators, violating both departmental and federal privacy requirements in the process. HSI’s practice of using administrative subpoenas to collect sweeping financial records from Western Union in several states since 2019 was exposed just last year. Senator Ron Wyden’s response to this issue pointed out the questionable authority and interpretations that HSI used to access these records, circumventing approval from the DHS Office of the General Council and Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties on several occasions to access bulk personal information.

From 2017 to mid-August 2022, HSI issued more than 170,000 custom summons for data, all without judicial oversight. Among these summonses, HSI sought records from a youth soccer league in Texas, surveillance footage from a major abortion provider in Illinois, state university health records services, student elementary school records in Georgia, and data from a Lutheran humanitarian aid organization supporting refugees. These summonses have also been used to target journalists. Despite the fact that HSI is required to tailor its subpoenas to current investigations only, HSI’s practices reveal that these powers have been used indiscriminately to amass bulk domestic surveillance databases. HSI uses its authority beyond its own stated mission.

Despite HSI and Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) being completely separate components of DHS, HSI uses its authority to conduct criminal investigations as a pretext for conducting deportations and family separation operations that ordinarily fall within ERO’s mandate. HSI has often enlisted its staff to aid in CBP and ERO deportation operations. This sort of cross-pollination leaves HSI’s expansive investigative powers accessible for use cases they were not intended to serve. HSI’s abuse of its authority is exacerbated by its ability to access and collect massive amounts of data.

HSI’s Surveillance Dragnet

HSI contributes to and retains access to several rich sources of surveillance data, and it has the authority to execute search warrants, court orders, and administrative subpoenas to collect information. ICE maintains a multi-billion dollarsurveillance data apparatus through the use of various surveillance technologies and access to several data sources and data analysis tools, including:

- Cell-site simulators (also known as Stingrays, or IMSI Catchers)

- Mobile application location data (high-precision location data from GPS signals, WiFi data, and cell tower triangulation) purchased from private data brokers, accessed through web apps

- GPS data (purchased from several data brokers) accessed through web apps

- License Plate Readers (LPR) and license plate data (acquired directly through HSI satellite facilities or purchased from data brokers)

- Utility records and other personal information (purchased from several data brokers including Thomson Reuters’ CLEAR (no longer active), LexisNexis’ Accurint and Special Services, and Equifax)

ICE has been able to access information from utility records through Thomson Reuters, accessing records across all 50 states for more than 218 million utility customers. In addition to ICE’s access to information through data brokers like Thomson Reuters, HSI collaborates with several local, state, and federal agencies to gain access to deep troves of personal data. ICE, including HSI, maintains access to TECS (where information can originate from other law enforcement agencies), the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Database, the DHS Enforcement Integrated Database (EID), and bulk DMV data which could include a person’s address, photos, vehicle registration and driver’s license number.

Several states and Washington, D.C. permit undocumented people to apply for driver’s licenses if they volunteer their personal information (including birth dates and addresses) in exchange. Analyzing the DHS’s extensive records, one report compiled some particularly troubling statistics exposing just how wide the DHS’ surveillance aperture actually is. The report notes that ICE has used facial recognition to scan the driver’s license photos of 1 in 3 adults and that ICE has access to the driver’s license data of 3 in 4 adults.

HSI’s broad surveillance apparatus and abuse of its legal authority give important context to the practical concerns with the agency’s Privacy Impact Assessment on surveillance technologies.

HSI’s Privacy Impact Assessment on Surveillance Technologies

A recent Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) published by the DHS in 2022 highlights HSI’s use of several categories of surveillance technologies, raising serious concerns surrounding HSI’s access to sensitive and overreaching data. This year, Government Accountability Office records indicated that HSI is already not adhering to the policies it set forward in this PIA.

This PIA specifically defines three categories of electronic interceptions and surveillance activities in which HSI engages:

- non-consensual surveillance, without a court order, when the surveillance does not intrude upon an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy;

- non-consensual electronic interceptions pursuant to a court order; and

- consensual electronic interceptions w/ consent of at least one party to the communication

Each of these categories present its own concerns given the systemic context HSI operates within and its history of not adhering to its own policies.

HSI’s narrow conception of a “reasonable expectation of privacy” (“REP”) runs counter to the Fourth Amendment and Supreme Court precedent.

HSI conducts non-consensual warrantless searches of people where HSI claims they have no reasonable expectation of privacy. No supervisory approval is required in cases of non-consensual surveillance in “public places.” The PIA declares that people do not have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in public spaces and defines public places as areas where the public has “unrestricted access and where no person has a reasonable expectation of privacy.” This definition is both circular, and far too broad.

The Supreme Court tells us that the Fourth Amendment “protects people, not places.” Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347, 351 (1967). It has defined the “reasonable expectation of privacy” with a sliding scale approach. Katz affirms that people can have a reasonable expectation of privacy in public spaces like phone booths. Other cases affirm that a reasonable expectation of privacy can extend to private homes, hotel rooms, rental cars (Byrd v. U.S.), medical diagnostic tests (Ferguson v. City of Charleston), workplace text messages (City of Ontario, Cal. v. Quon), and cell site location information (Carpenter v. U.S.). Though people may not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their movements in public places like roads and public transit (Knotts), the bulk collection of location information by monitoring people through GPS trackers (U.S. v. Jones) or digital data collection (Carpenter v. U.S.) can still constitute unreasonable searches and seizures of people in public spaces.

This is an inherently normative evaluation—the Supreme Court’s precedent aims to reflect current norms, and in turn, shapes the expectations people have around privacy. ICE’s blanket definition of where a reasonable expectation of privacy (REP) applies (and by extension, may not apply) not only reflects an outdated view of REP applying to places, but also does not meaningfully address ICE’s ability to effortlessly, quietly, and cheaply collect bulk records on individuals, preserve them indefinitely, and tile them into rich and revealing mosaics that evade ordinary checks that constrain abusive law enforcement practices. US v Jones, Sotomayor concurrence citing Illinois v. Lidster. These bulk data caches form readily queryable passive surveillance systems at scale.

A 2010 ICE HSI Handbook on Search and Seizure states explicitly that the mounting of pole cameras that look into the yards of private persons is an acceptable warrantless search (§ 5.9.3).[1] It declares that if an agent can see, hear, or otherwise observe something from a vantage point of a public place where they have lawful access, that they “may see, listen to, or observe the same evidence using technological aids in order to observe the evidence more clearly or keep their investigation clandestine.” But the fundamental premise of technological aids is that they can collect richer, crisper, and indefinite records in places that a human observer could not reasonably gather. Cameras do not need to go offline to eat, sleep, or go to the bathroom, and the cameras are hidden in plain sight. While binoculars and telescopes are not permitted for warrantless searches, always-on cameras are. The premise that HSI’s ability to perform non-consensual surveillance is reasonably constrained by REP is clearly flawed.

The PIA states that “a search warrant may be required to operate a camera that monitors an area where an individual has a reasonable expectation of privacy[,]” but this does not constrain HSI’s ability to leverage titanic corpuses of commercial data, nor HSI’s ability to deploy small drones (UAS systems) to surveil on individuals for continuous stretches of time.

Law enforcement officers’ capacity to collect data from people’s existence in public places has had a meaningful chilling effect for over 23 million U.S. residents. A study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that the fear and uncertainty that undocumented families live in had led to them limiting their driving to lower the chances of having inadvertent interactions with police. They have also tried to keep their kids indoors as much as possible, leaving once-vibrant playgrounds suddenly vacant.” Police departments have observed sharp decreases in reported domestic violenceand abuse among Latinos in places like Los Angeles, where women must choose whether they want to risk deportation or domestic violence. Waiting rooms were less full than they were previously at health clinics serving undocumented immigrants in South Texas, after Trump took office. Across the country, immigrant families are reluctant to sign their children up for school lunch programs out of fear of targeting. And where labor conditions impose demanding and inhumane conditions on child migrant workers, families do not challenge this exploitation out of fear of deportation.

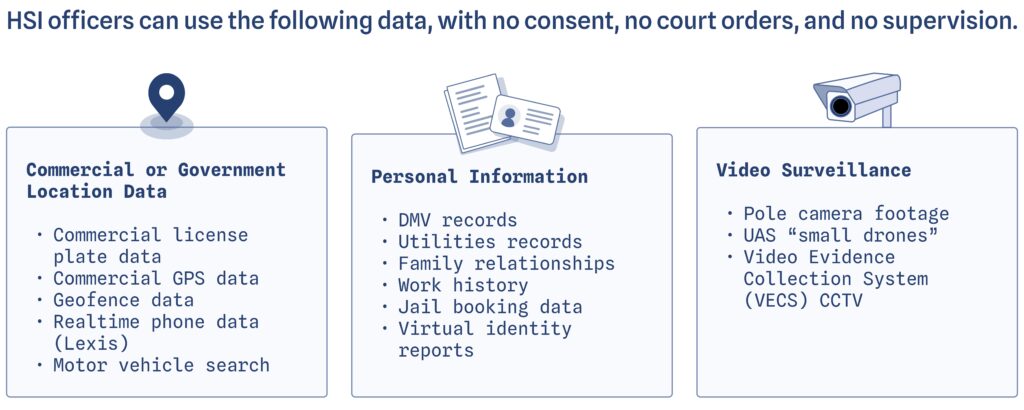

SOURCES: LexisNexis reporting and LexisNexis usage logs, Jail booking data, American Dragnet, PIA

The boundaries between what HSI can access with and without a warrant are blurry.

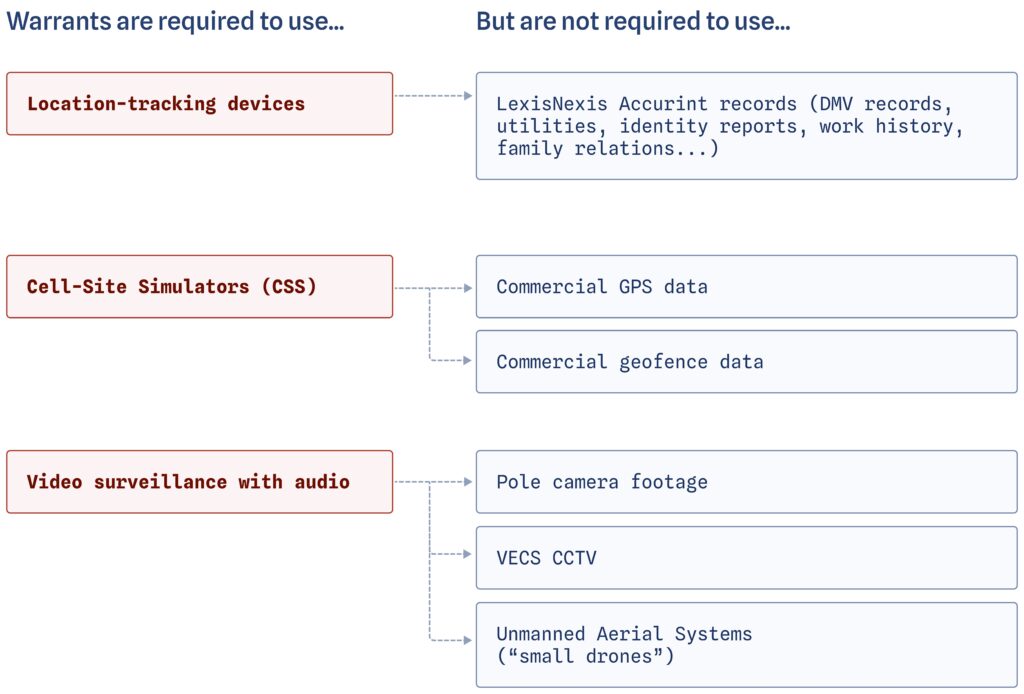

With ICE HSI’s ability to reach into prying records like utilities, DMV data, and GPS data, its access to non-consensual warrantless surveillance is virtually unconstrained. ICE HSI cannot directly intercept “oral, wire, or electronic communication” from targeted devices (including phones, computers and emails) or use location-tracking technology[2]without probable cause and a court-issued warrant. But these restrictions do not expressly apply to the use of commercially available data that can be just as, or in some cases more, invasive. Still, HSI can mount pole cameras and use small drones in “public spaces” while functionally still tracking an individual’s movements all without a warrant. HSI requires different procedures for (1) putting a GPS tracker physically on a person or their vehicle and (2) enabling aerial tracking via a drone. And when HSI case agents do not seek warrants, they can turn to commercial data brokers, fueling the growth of surveillance for-profit systems.

HSI has already violated policies it established in this PIA. Other policies remain vague.

Cell-Site Simulators (CSS) are listed as one of the non-consensual surveillance techniques that requires a warrant. But, in exigent circumstances, the PIA establishes an exemption from supervisory approvals. This exception does not exempt officers from warrant requirements altogether. When discussing CSS policies, the PIA stated that “[w]hen an officer has the requisite probable cause, a variety of exigent circumstances may justify dispensing with a warrant.” Later, the PIA clarified that in emergency situations, case agents must still apply for court orders within 48 hours of installing CSS pursuant to statutory requirements. This clarification was delivered by a single line twenty-two pages after CSS procedures were listed. A similar pattern applies to the PIA’s discussion of location tracking technology.

Issues of vagueness evidently extend to other HSI CSS internal policies, too. In 2023, the OIG found several issues with ICE HSI’s deployment of CSS, including:

- Insufficiently detailed guidance on how agents could work with external law enforcement agencies.

- Interpreting policies in ways that did not reflect HSI’s statutory requirement to obtain warrants before using CSS or applying for it within 48 hours of installation efforts.

- Failure to adhere to its own privacy policy that requires CSS to have an approved PIA before use.

This is not the first time HSI did not adhere to internal policies. In December 2018, a GAO audit found that HSI case agents did not consistently follow procedures when handling veterans’ removal cases “because they were unaware of the policies prior to [the] review.” Those two requirements were established in 2004 and 2015.

The lack of detailed guidance on how agents can work with law enforcement agencies raises several concerns. The boundaries between HSI and ERO are already blurry, and ERO itself has delegated enforcement powers to local law enforcement agencies across the country, often to sheriffs with records of violent and discriminatory behavior, while “[lacking] an oversight mechanism.” ERO cannot execute search warrants, but HSI can. It is also unclear throughout the PIA whether other participants of HSI information sharing initiatives are bound by the same requirements that ICE HSI case agents are when deploying location tracking technologies.[3] HSI maintains access to several data systems and can control access for partner law enforcement agencies to data housed under the National Tracking Program.

ICE is currently facing staffing shortages, forced overtime, declining morale and changing policies. These threaten to deepen confusion about what policies are currently in effect and raise questions as to whether case agents can actually meet the burdens required of them to appropriately use surveillance technologies.

HSI’s discussion of consent-based surveillance does not address the deceptive tactics ICE has historically used.

The PIA permits the consensual interception of an “oral, wire, or electronic communication” when it can establish “one party consent.” Only one party to a conversation needs to give prior consent to the data interception in these cases. This rule extends to HSI undercover special agents. The PIA also states that “[c]onsensual video surveillance may be conducted in a warrantless manner even though one party to the conversation may have a reasonable expectation of privacy.” Taken together, this permits ICE agents to unilaterally gain access to communications information. This is a deeply concerning policy given the well documented history of ICE agents using deceptive tactics and covert operations. The ACLU has reported that “ICE agents have impersonated police, disguised themselves as day laborers, represented themselves as probation officers and tricked people into locating a family member.” By inserting themselves into tenuous situations using deceptive tactics, HSI agents create the “consent” required.

Conclusion

HSI case agents’ broad ability to access and use commercially available data with no consent, no court order, and no supervision creates undo privacy risks ignored by the Privacy Impact Assessment. And while some safeguards show promise, like the limits on data collection on CSS devices, continued access to publicly available information and commercial data weakens these purported safeguards. In the end, ICE’s Privacy Impact Assessment on surveillance technologies treats ICE’s surveillance as if it occurs in a vacuum, unconnected to other means to obtain the same surveillance data without oversight. It fails to provide the full picture of privacy risks associated with ICE surveillance and consequently fails to offer meaningful mitigation of these privacy risks.

[1] “Placement of a surveillance camera (without audio) in a public place (i.e., a location where an individual does not have a reasonable expectation of privacy) is an investigative activity that does not require a warrant so long as the camera is placed with any required permissions of the property owner. A ‘public place’ is an area where the public has unrestricted access and where no person has a reasonable expectation of privacy. 27 Public places can include public streets, public parking lots, and hallways of a building open to the public. However, depending on a number of factors, a search warrant may be required to operate a camera that monitors an area where an individual has a reasonable expectation of privacy.”

[2] ICE HSI’s use of location-tracking technology generally requires a warrant issued with probable cause. “Authorization to use a tracking device in consensual and non-intrusive installation situations requires a warrant absent certain circumstances (e.g., consent, exigency) and must also be approved by both the agent’s first-line supervisor and second-line supervisor.”

[3] The PIA states that the “National Tracking Program may share data with other approved law enforcement agencies consistent with the terms and conditions agreed to by the National Tracking Program and the other law enforcement agency.” This language seems to imply that HSI may first obtain data using its own policies and procedures, but other agencies may leverage the same data under different requirements that may not include warrants or probable cause at all.

Support Our Work

EPIC's work is funded by the support of individuals like you, who allow us to continue to protect privacy, open government, and democratic values in the information age.

Donate