APA Comments

In the Matter of Empowering Broadband Consumers Through Transparency (FNPRM)

CG Docket No. 22-2 (Feb. 2023)

COMMENTS ON

FURTHER NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING

by

Center for Democracy & Technology

Electronic Privacy Information Center and

Ranking Digital Rights

February 16, 2023

Table of Contents

I. Broadband Labels and Privacy Policies

a. The Commission Should Implement Three Simple Notices in the Privacy Section of the Label

b. The Commission Should Explicitly Clarify Its Expectations for Providers’ Privacy Policies

II. The Commission Should Require Disclosures from Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs) to Ensure Consumers are Informed About All Data Uses

III. The Commission Has Legal Authority to Require These Disclosures

IV. Conclusion

Summary

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT), and Ranking Digital Rights (RDR) applaud the Commission’s steps in its Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (FNPRM) to provide consumers with transparent, easy-to-understand notice of broadband providers’ data practices.[1] Simplified privacy notices will empower consumers to make informed choices among providers and are a necessary step to fulfill Congressional intent in directing the Commission to provide transparency labels for broadband service.

EPIC is a public interest research center in Washington, D.C. EPIC was established in 1994 to focus public attention on emerging privacy and related human rights issues, and to protect privacy, the First Amendment, and constitutional values. EPIC advocates for rules that protect consumers from exploitative data practices. CDT is a 27-year old 501(c)(3) nonpartisan nonprofit organization that fights to put democracy and human rights at the center of the digital revolution. It works to promote democratic values by shaping technology policy and architecture, with a focus on equity and justice. RDR is an independent research program founded in 2013; it promotes freedom of expression and privacy on the internet by creating global standards and incentives for companies to respect and protect user’s rights.

We urge the Commission to take three actions in light of the issues raised in the FNPRM:

- Update its nutrition labels with three simple notices regarding the collection and use, sharing, and opt-out rights with respect to consumer data. Simple notices provide consumers critical information, rather than leaving consumers to navigate cumbersome privacy policies themselves, if they review them at all. These notices are critical for consumers to understand whether behavioral profiles are being created or updated using their browsing history or location data, and whether this information is being shared with third parties. In addition, the Commission should consider mandating a fourth disclosure, regarding data practices that pose elevated risks to consumers, such as behavioral advertising based on protected classes.

- Explicitly clarify what providers must include in the privacy policies they link to from the broadband nutrition label. In its Restoring Internet Freedom Order, the Commission made privacy policies a key component of its Transparency Rule. The Commission should now clarify what those policies should disclose, including, at minimum, the collection of non-essential data, disclosure of that data, user rights, use of encryption or other security measures, and use of algorithmic systems to make critical decisions regarding consumers.

- Address how a mobile virtual network operator (MVNO) should account for the data practices of the facilities-based providers whose networks the MVNO uses. The Commission can ensure that the customers of MVNOs are informed of the uses of their data by requiring MVNOs’ notices on the broadband label either to disclose the data practices and policies of the providers of its underlying networks or to disclose what data it contractually permits facilities-based providers to collect, use, and share.

I. Broadband Labels and Privacy Policies

We appreciate the Commission soliciting input on including more information in the privacy section of its label in the near future, although we disagree with the Commission’s decision to permit a broadband provider to provide a mere link to its privacy policy for the time being. We support the three notices suggested by the Commission in the FNPRM — whether the provider uses or discloses consumer data for reasons other than providing broadband service, whether the data is shared with third parties, and whether consumers can opt out of those practices. To ensure that consumers can be fully informed about providers’ data practices, we urge the Commission to clarify explicitly what minimum information it expects providers to include in the privacy policies they link to from their respective nutrition labels.

a. The Commission Should Implement Three Simple Notices in the Privacy Section of the Label

We support the Commission’s proposal to include the collection, use, and disclosure of consumer data for purposes other than providing broadband service in the broadband labels as detailed in the FNPRM.[2] These simple notices would be in addition to a link to the provider’s full privacy policy, and would better fulfill the labels’ key purpose to provide consumers “access to clear, easy-to-understand, and accurate information.”[3]

Empirical research demonstrates that simple, accessible notices are both needed and effective. As Dr. Lorrie Faith Cranor noted in the Second Virtual Public Hearing on the notices, consumers are unlikely to click through links in the nutrition label.[4] Even if they were, it would take a person 244 hours to review all privacy policies a person typically encounters in a year.[5] National surveys show that people care about what companies do with their data — for example, one Pew Research survey revealed that 81 percent of Americans believe that the risks of companies collecting their personal data outweigh the benefits; yet, 59 percent have “little/no understanding” about what companies do with the data collected.[6] Empirical research, including that led by Dr. Cranor, shows that consumers find tables or labels describing policy practices more useful than full privacy policies.[7] In one study, internet users were provided different kinds of privacy notices, including a table or label and a full privacy policy, and were asked to answer questions based on the disclosures. Respondents using the table format were able to better:

- identify data that is beyond the scope of the policy;

- identify data not collected;

- identity sensitive data collections; and

- understand when data is disclosed.[8]

Another study asked participants in focus groups and laboratory studies to compare privacy notices in an expandable grid, a simplified grid, and a simplified label with yes/no disclosures.[9] In that study, respondents using the label were able to answer questions more accurately, find information more quickly, and better select policies reflecting stronger privacy practices.[10]

Because consumers are better able to understand data collection and sharing practices based on simple disclosures, privacy disclosures on the broadband label can directly address harms that stem from broadband providers’ data practices. As explained elsewhere in the record,[11] providers’ collection of data for purposes other than providing broadband service can harm consumers. A 2021 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) staff report details troubling data practices by the country’s largest providers.[12] The FTC found that many providers collect and then combine a host of individualized data about their customers across their products, including the websites that customers visit, the shows they watch, the apps they use, details about home energy use, their real-time and historical location, internet search queries, and even the content of communications.[13] Providers then use this broad array of data for purposes other than providing broadband services. Providers log and retain data, like data associated with web browsing or television viewing history, to build and maintain behavioral profiles about consumers for better advertising targeting.[14] At least half of the broadband providers the FTC examined engage in cross-device tracking, a practice that consumers will not necessarily understand and could even violate consumer expectations because people expect that their devices will be kept separate.[15]

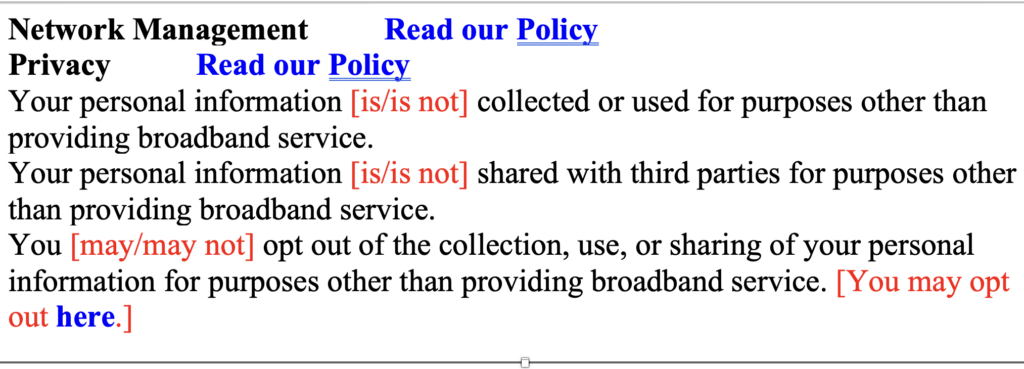

The three simple disclosures suggested by the Commission in the FNPRM would help alert consumers to these practices. We encourage the Commission to implement those notices in three simple yes/no statements in the privacy section of its label, asking: (1) whether the provider collects or uses consumer data for reasons other than providing broadband service;[16] (2) whether the provider discloses consumer data to third parties for reasons other than providing broadband service, and (3) whether the consumer can opt out of this collection, use, and sharing.[17] That information could be displayed on the label as follows:

The Commission should make clear that what constitutes “providing a broadband service,” is limited to functions such as billing, customer service, tech support, or related internal business operations, and the use of subscriber data for compliance with lawful process (e.g., a court-ordered warrant), for fraud detection and cybersecurity efforts, and for product development and testing.[18]

Moreover, “providing a broadband service” does not include certain data practices such as behavioral advertising. The use of subscriber data to create or update behavioral profiles[19] falls within neither “internal business operations” nor “development and testing” and would require — at minimum — an affirmative answer to the collection or use question on the label. Further, to the extent a data practice poses elevated risks to consumers, the Commission should consider mandating an additional disclosure on the label of those practices. For example, the FTC has described some providers’ practices of placing consumers in segments based on protected classes or sensitive information, such as “viewership-gay,” “pro-choice,” “African American,” “Assimilation or Origin Score,” “Jewish,” “Asian Achievers,” “Gospel and Grits,” “Hispanic Harmony,” “tough times,” and “seeking medical care.”[20] Likewise, many broadband providers collect 100% of consumers’ unencrypted internet traffic, including visits to sensitive websites related to health, LGBTQ+ status, and domestic violence.[21] As the FTC concluded, behavioral advertising “rais[es] questions about how such advertising might (1) affect communities of color, historically marginalized groups, and economically vulnerable populations, or (2) reveal sensitive details about consumers’ browsing habits.”[22] Those practices are non-essential to providing broadband service, require an affirmative notice on the label’s collection or use question, and may merit additional notices as determined by the Commission.[23]

To ensure consumers are not misled, the Commission should explicitly state that sharing data with affiliates and parent companies for purposes such as building behavioral profiles and targeted advertising (but not customer service, tech support, fraud detection, and similar internal business operations) would qualify as sharing subscriber data with a third party and would require an affirmative answer to the sharing question on the broadband nutrition label.[24]

Regarding opting out, the FTC has identified serious obstacles consumers may face when attempting to opt out of data collection (to the extent the broadband provider permits opting out in the first place).[25] The Commission should consider issuing joint guidance with the FTC on when obstacles for consumers to opt out of providers’ data practices amount to the provider constructively not permitting consumers to opt out at all.

We also urge the Commission to gather information about how providers use contracts to limit partner use of subscriber data,[26] and how practices like this might better protect consumers. Downstream providers of phone carriers committed serious abuses of consumer information prior to 2020;[27] understanding how to prevent this in the future would greatly benefit consumers. We encourage the Commission to be proactive in inquiring about these relationships and how broadband providers manage those relationships to protect the interests of their subscribers.

b. The Commission Should Explicitly Clarify Its Expectations for Providers’ Privacy Policies

We ask the Commission to explicitly require providers to include certain disclosures in their privacy policies. In its Report and Order in this proceeding, the Commission noted that thorough privacy policies are important considerations to consumers[28] and reiterated that the 2017 Restoring Internet Freedom Order (“2017 Order”) is the current directive regarding privacy policy disclosures.[29] The 2017 Order explicitly required “complete and accurate disclosure about the [internet service providers’] privacy practices, if any. For example, whether any network management practices entail inspection of network traffic, and whether traffic is stored, provided to third parties, or used by the ISP for non-network management purposes.”[30] Thus, the Commission should require providers to include in their privacy policies, at minimum:

- what data they collect, use, and retain beyond what is essential to provide broadband service, and the purposes for that collection, use, and retention;

- what data they disclose to third parties for purposes other than providing broadband service, and the purposes for that disclosure;

- whether they use consumer data in the development of algorithmic systems or rely on algorithmic decision-making to make critical decisions regarding consumers, such as creditworthiness;[31]

- whether they encrypt stored consumer data; and

- what rights consumers have to opt-out of these practices and to correct or delete their data.

II. The Commission Should Require Disclosures from Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs) to Ensure Consumers are Informed About All Data Uses

Last year Chair Rosenworcel published the response letters from mobile carriers[32] to Letters of Inquiry[33] regarding the collection and use of consumer geolocation data. These response letters underscored just how many providers (approximately half) are mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs). Many of those MVNOs indicated that while they may not collect specific data, the facilities-based providers whose networks they utilize might. This difference is significant because a consumer may read the nutrition label for an MVNO, not realizing that the practices of facilities-based providers may also be relevant to use of the consumer’s data.[34]

The Commission must ensure that the consumer has a chance to understand all relevant information regarding how their data will be handled. We urge the Commission to require that MVNOs’ labels reflect the practices and policies of any and all vendors or upstream providers who may be accessing consumer data so that consumers may understand what entities are processing their data and how it is used. This may require the Commission issuing guidance for MVNOs’ implementation of the labels, such as having separate sections on the label for the practices of the MVNO and of the facilities-based providers.

Alternatively, the Commission could require each MVNO to state what data it is contractually required to provide to its vendors, upstream providers, and partners, and to update its labels whenever this changes (including when a new network is signed on that has its own privacy and data collection policies). This means that each MVNO must provide notice as to what its contracts allow its facilities-based providers to do with consumer data.

III. The Commission Has Legal Authority to Require These Disclosures

As the Commission has recognized — and as detailed elsewhere in the record[35] — the Commission has the legal authority under the Communications Act to require privacy notices on broadband labels. Section 13 of the Communications Act, as amended, requires the Commission to publish a biennial report on the “state of the communications marketplace.”[36] The Act, however, “does not specify precisely how [the Commission] should obtain and analyze information for purposes of its reports,” and it may reasonably be interpreted as “including within it direct authority to collect evidence” regarding the communications marketplace.[37] Based on this reading of the Act, the D.C. Circuit has affirmed the Commission’s current “transparency rule,”[38] which requires broadband providers to “publicly disclose accurate information” regarding their “commercial terms,”[39] including privacy practices.[40]

Simplified privacy notices are also within the Commission’s mandate under Section 60504 of the Infrastructure Act.[41] Section 60504(c) required the Commission to assess whether “disclosures required under section 8.1 of title 47, Code of Federal Regulations, are available, effective, and sufficient.”[42] As the Commission has explained, providers’ privacy practices are a component of those disclosures;[43] Congress’s intent in Section 60504 was plainly not to lock the Commission into simply reinstating the 2016 labels, but to consider how they could be improved. Privacy is a key component of providers’ required disclosures both under Rule 8.1 and on the labels, and the Commission should take steps in light of Section 60504’s mandate and the FNPRM to make providers’ privacy disclosures more available, effective, and sufficient.

IV. Conclusion

We appreciate the opportunity to comment on the Commission’s efforts to ensure consumers are able to make informed purchasing decisions when choosing among competing broadband providers.

[1] Empowering Broadband Consumers Through Transparency, CG Docket No. 22-2, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, FCC 22-86, para. 2 (Nov. 17, 2022) (Transparency Order).

[2] Transparency Order, para. 58 (“We nevertheless recognize that privacy policies and practices, such as whether a provider discloses data to third parties, whether providers collect and retain data about consumers that may not be essential to providing the consumer with broadband service (e.g., the websites the consumer visits), and whether customers can opt out of each data practice, are important.”); id., paras. 146-47.

[3] Transparency Order, para. 1; accord id., Statement of Chairwoman Rosenworcel (“[Y]ou shouldn’t have to be a lawyer to know just what is in your internet service plan or an engineer to understand just how your provider is treating your data.”). The Order and Commissioners recognized that the labels would have to be continued to be improved over time. Transparency Order, para. 67 (“Our conclusion does not mean we think the labels should be static.”); id., Statement of Commissioner Starks (“[W]e shouldn’t rest on our laurels. We must continue to listen to the record to improve the labels, if necessary.”).

[4] Broadband Consumer Labels 2nd Virtual Public Hearing, Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n at 1:16:52 (Apr. 7, 2022) (statement of Prof. Lorrie Cranor), https://www.fcc.gov/news-events/events/2022/04/broadband-consumer-labels- 2nd-virtual-public-hearing (“I think we should assume that most consumers will never click through, and the reason to have the clickthrough information is for experts not for consumers.”). A recent study by the FTC estimates that fewer than 7% of subscribers visit their broadband provider’s privacy policy. Fed. Trade Comm’n, A Look At What ISPs Know About You: Examining the Privacy Practices of Six Major Internet Service Providers 27 (2021), available at https://www.ftc.gov/reports/look-what-isps-know-about-you-examining-privacy-practices-six-major- internet-service-providers (FTC ISP Report).

[5] Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor, The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies, 4 I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, no. 3, 543-568 (Winter 2008/2009), available at https://lorrie.cranor.org/pubs/readingPolicyCost-authorDraft.pdf

[6] Brooke Auxier et al., Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused and Feeling Lack of Control Over Their Personal Information, Pew Research Center (Nov. 15, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/ americans-and-privacy-concerned-confused-and-feeling-lack-of-control-over-their-personal-information/.

[7] Patrick Gage Kelley et al., Standardizing Privacy Notices: An Online Study of the Nutrition Label Approach, Privacy Roundtables – Comment, Project No. P095416 (2010), available at https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/ documents/public_comments/privacy-roundtables-comment-project-no.p095416-544506-00037/544506-00037.pdf.

[8] Id. at 6-9.

[9] Patrick Gage Kelley et al., A “Nutrition Label” for Privacy, Symposium On Usable Privacy and Security (2009), available at https://cups.cs.cmu.edu/soups/2009/proceedings/a4-kelley.pdf.

[10] Id. at 9-11.

[11] CDT Reply at 2-5.

[12] FTC ISP Report, supra note 5. Some of the privacy concerns identified in this report have already been cited in several comments in this docket. See CDT Reply at 2; EPIC at 6; Cloudflare at 3; RDR at 4; OTI at 7.

[13] FTC ISP Report at 34.

[14] FTC ISP Report at 35.

[15] Id. at 36.

[16] This should be limited to what is essential to provide broadband service, as a recent study by the Federal Trade Commission found that there is significant variability in how providers define business purposes. See FTC ISP Report at 31 (noting that although some providers purport to collect, retain, or disclose data for a “business reason,” use of the term varied widely).

[17] There are alternative approaches for how this might be presented in a label as well. See, e.g., Comments of EPIC at 10.

[18] See, e.g., FTC ISP Report at 16.

[19] FTC ISP Report at 18 (reporting on broadband provider’s use of app usage history and web-browsing data for targeted advertising, and appending demographic information including gender, age, race and ethnicity, marital status, and parental status); id. at 33 (noting vertical integration can result in highly granular data being collected by combining data from broadband services with services including home security, video streaming, wearables, and connected cars); id. at 35-38 (including cross-device tracking, using and selling location information for advertising purposes, and “digital redlining” which may result from race and ethnicity-based target advertising); id. at 35 (consumers rank browsing history in top five most important pieces of personal information).

[20] FTC ISP Report at 22.

[21] See FTC ISP Report at 42-43.

[22] FTC ISP Report at 22.

[23] A fourth disclosure may appear as “Your personal information [is/is not] collected or used for the purpose of behavioral profiles or advertising” or “We [do/do not] collect, use, or share your sensitive information, such as race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, family status, income, or age.”

[24] See FTC ISP Report at 27 (“[T]hree of the ISPs in our study reserved the right to share their subscribers’ personal information with their parents and affiliates, which seems to undercut the promise not to sell personal information.”).

[25] See FTC ISP Report at 39-41.

[26] FTC ISP Report at 26.

[27] FTC ISP Report at 25 (citing FCC Proposes over $200M in Fines for Wireless Location Data Violations, Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n (Feb. 28, 2020), https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-proposes-over-200m-fines-wireless- location-data-violations).

[28] Transparency Order, para. 57.

[29] Transparency Order, para. 58.

[30] Restoring Internet Freedom, WC Docket No. 17-108, Declaratory Ruling, Report and Order, and Order, 33 FCC Rcd 311, 442, para. 223 (2018) (2017 Order).

[31] For more on algorithmic decision-making, especially regarding critical opportunities such as access to or advertising for housing, credit, and employment, see Ridhi Shetty et al., Center for Democracy & Technology, CDT Comments to FTC Regarding Prevalent Commercial Surveillance Practices that Harm Consumers 25-36 (2022), https://cdt.org/insights/cdt-submitted-testimony-regarding-d-c-stop-discrimination-by-algorithms-act.

[32] Rosenworcel Shares Mobile Carrier Responses to Data Privacy Probe, Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n (Aug. 24, 2022), https://www.fcc.gov/document/rosenworcel-shares-mobile-carrier-responses-data-privacy-probe.

[33] Rosenworcel Probes Mobile Carriers on Data Privacy Practices, Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n (July 19, 2022), https://www.fcc.gov/document/rosenworcel-probes-mobile-carriers-data-privacy-practices.

[34] See T. Scott Cowperthwait, Vice President, Law – Policy and Cybersecurity, Charter Communications, to Jessica Rosenworcel, Chairwoman, Federal Communications Commission 2 (Aug. 3, 2022), available at https://www.fcc.gov/document/rosenworcel-shares-mobile-carrier-responses-data-privacy-probe (noting that facilities-based provider has access to MVNO customers’ location data).

[35] CDT Reply 7-10.

[36] Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, sec. 401, § 13(a), 132 Stat. 1087-88 (2018) (codified at 47 U.S.C. § 163).

[37] Mozilla Corp. v. FCC, 940 F.3d 1, 47 (2019)

[38] Id.

[39] 47 C.F.R. § 8.1(a).

[40] 2017 Order, para. 223.

[41] Transparency Order, para. 57 (“[W]ithout going beyond the scope of the charge given to us by Congress in section 60504 of the Infrastructure Act . . . it is premature to revise the 2016 labels’ privacy disclosure.”)

[42] Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Pub. L. No. 117-58, 135 Stat. 429, § 60504(c) (2021).

[43] 2017 Order, paras. 215-38.

Support Our Work

EPIC's work is funded by the support of individuals like you, who allow us to continue to protect privacy, open government, and democratic values in the information age.

Donate