APA Comments

Reply Comments in re: Data Breach Reporting Requirements

WC Docket No. 22-21 (Mar. 2023)

Before the

FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION

In the Matter of Data Breach Reporting Requirements

REPLY COMMENTS ON

NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING IN

WC DOCKET NO. 22-21

by

Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC),

Center for Democracy and Technology,

Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, and

Public Knowledge

Submitted March 24, 2023

Summary

The cyber threat environment in 2023 is significantly worse than it was in 2016. The Federal Communications Commission must prioritize protecting consumers by incentivizing the industry to improve its data security practices, by offering the industry guidance based on trends the Commission sees from its required breach reporting, and by equipping consumers to protect themselves when their data has been compromised.

These reply comments emphasize that a harm-based trigger inhibits the ability of consumers to protect themselves because it overlooks that unauthorized access of their data is inherently harmful and instead relies on a company’s estimation of whether that harm will result in a financial loss. Carriers aren’t incentivized to be impartial; such a ‘likely harm’ estimate would be performed by the same carrier that failed to properly weigh costs vs. benefits in preventing the breach itself.

These reply comments also address equity issues for Telecommunications Relay Service (TRS) users, ensuring they are guaranteed the same levels of protection any user in a similar position would expect—namely that the content of their communications is not exempt from a carrier’s obligations to safeguard the privacy and data security of its subscribers.

The scope of what constitutes a “customer” should include anyone who has provided information to the carrier, such as former and prospective customers (not merely Lifeline applicants, as described in EPIC’s February 22, 2023 comment). These reply comments also provide additional examples of the Commission protecting types of data beyond the factors listed in Section 222(h) using its authorities under Section 222 and Section 201(b) of the Communications Act.

We strongly support the Commission’s attempts to elevate the trajectory of telecom data security and urge the Commission to maintain consumer safety as the core goal of this proceeding.

I. Introduction

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT), Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, and Public Knowledge (“Public Interest Advocates”) file these reply comments to applaud the Federal Communications Commission (“Commission” or “FCC”) for its attention to the increasingly severe and largely avoidable impacts of data breaches on phone subscribers and to urge the Commission to enact regulations that:

- equip consumers to mitigate downstream harms resulting from data breaches;

- inform the Commission’s staff of possible network vulnerabilities;

- incentivize a higher standard for what constitutes basic data security practices to prevent consumer data from breached in the first place; and

- re-iterate and clarify the scope of the Commission’s privacy authorities.

EPIC[1] is a public interest research center in Washington, D.C., established in 1994 to secure the fundamental right to privacy in the digital age for all people through advocacy, research, and litigation. EPIC has long defended the rights of consumers and has played a leading role in developing the Commission’s authority to address emerging privacy and cybersecurity issues.[2] EPIC routinely advocates before the Commission for rules that protect consumers from exploitative data practices.[3]

The Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT)[4] is a non-profit advocacy organization working to promote democratic values online and in new, existing, and emerging technologies.

Privacy Rights Clearinghouse (PRC)[5] is a nonprofit organization based in San Diego, California, established in 1992 to advance privacy for all by empowering individuals and advocating for positive change. PRC has championed strong data breach notification laws since 2005, when the world’s first such law was passed in California. PRC also maintains the Data Breach Chronology,[6] an extensive and widely accessible database of publicly-reported U.S. data breaches, and publishes educational materials to help people understand existing rights and choices.

Public Knowledge[7] promotes freedom of expression, an open internet, and access to affordable communications tools and creative works.

In these reply comments, Public Interest Advocates highlight a pattern of systemic data security and breach notification deficiencies, urge the Commission to clarify its broad privacy authorities, provide context demonstrating that the Commission’s mandate to protect Customer Proprietary Network Information (CPNI) is grounded in consumer privacy concerns moreso than in competition considerations, update the factual record regarding the increasingly severe cyber threat environment, support protections for TRS users, articulate why consumers must be informed of a breach independently of a company’s determination of likely harm, urge the Commission to clarify that former customers and others are included in its definition of “customer”, and encourage the Commission to explore privacy protections for users of web-enabled vehicles.

II. There is Evidence of Systemic Problems that Demand Commission Action.

The Commission has stated that “[i]n the telecommunications industry, the public has suffered an increasing number of security breaches of customer information in recent years.”[8] Some commenters have claimed that employee accidents cause no harm, or assert that there is no evidence of a problem,[9] or argue for a good faith exception.[10] However, these contentions are belied by both Commission policy and recent reality. There is clearly evidence of harm resulting from employee “accidents”—in February 2020, the failure of carriers to enforce the terms of their own contracts with location aggregators led to one of the largest and longest-lasting breaches of phone subscriber location data, prompting the Commission to issue more than $200 million in Notices of Apparent Liability (NALs).[11] This misconduct occurred and went unreported despite the force of 50-plus mandatory data breach notification laws at the state level.[12] As for a good faith exception, EPIC petitioned the Commission in 2005 precisely because employees, either through bribery or inadequate training, were illegally disclosing consumer information to pretexters claiming to have authorization to access subscriber information.[13] The current definition of breach reflects an understanding of this problem, which incorporates “intentionally gained access” language, as a direct result of the rulemaking the Commission took up in response to EPIC’s petition.[14] More recently, in 2015 and again in 2019, major news outlets reported on carrier employees accepting money in exchange for illegally disclosing subscriber information.[15] In short: employee “accidents” and good faith exceptions should not be a reason to weaken privacy and data security protections for consumers.

There are clearly systemic data security problems in this industry that demand Commission action, and we applaud the Commission for initiating this rulemaking to address them. However, in addition to this rulemaking, we take this opportunity to urge the Commission to promptly issue forfeiture orders for the above-mentioned February 2020 NALs.

III. Commission Enforcement and Rulemaking Have Long Established that the FCC’s Mandate Includes Personal Information.

The Commission has stated that “telecommunications carriers possess proprietary information other than CPNI that customers have an interest in protecting from public exposure, such as Social Security Numbers and financial records.”[16] Some commenters have claimed that the Commission’s privacy authority is limited to the specific categories of CPNI listed in Section 222(h), and that this excludes information collected by carriers that would otherwise by PII, such as social security numbers.[17] This argument fails for multiple reasons. First, and most importantly, the Commission previously addressed this argument and unambiguously defined all PII that comes into a carrier’s possession by virtue of the carrier/customer relationship as CPNI in the 2007 Pretexting Order.[18] The time has long past for carriers to challenge this well-established holding.

Even if the matter were open to re-examination, the language of Section 222 supports including personally identifying information—as the Commission has previously established.[19] Section 222(h) describes as CPNI any information that “relates to the quantity, technical configuration, type, destination and amount of use” (emphasis added) of the relevant telecommunications service. Collection of personal information to establish whether a customer can afford a particular service or to determine the customer’s creditworthiness are just two examples of collection of personal information clearly “related to” the type of service or amount of use provided by the carrier. Even where this not the case, the Commission has also stated that Section 222(a)’s obligation to protect any and all “proprietary information of and relating to . . . customers” imposes a general duty on carriers to protect personally identifying information or other information provided by customers that goes beyond the listed characteristics of CPNI. Finally, even if the Commission did not find the authority in Section 222 sufficiently broad, the Commission has established that pursuant to Section 201(b), the disclosure of personally identifying information—especially highly sensitive information such as social security numbers—is unjust and unreasonable.[20] Not only has the Commission clearly established its jurisdiction over personal information beyond the factors in 222(h), but it has also established its privacy authority under Section 201(b).

IV. The Commission’s Privacy Authority Extends Beyond the Express Factors Listed in 222(h).

For many years (and as recently as eight months ago), the Commission has declined to limit the scope of its privacy authority to the factors listed in Section 222(h), holding that carriers must safeguard a wider spectrum of personally identifiable information (PII) and other personal data. In August 2022, the Commission reiterated that “[t]he scope of “proprietary information” covered by section 222 extends beyond CPNI data to include private or sensitive data that a customer would normally wish to protect.”[21] This includes (but is not limited to) data which would risk physical, emotional, or reputational harm if exposed.[22] In March 2022, the Commission cited to the TerraCom case for the understanding that PII is “information that can be used on its own or with other information to contact, or locate a single person, or to identify an individual in context.”[23] In the same enforcement action, the Commission reiterated that all communications service providers “[have] a statutory responsibility to ensure the protection of customer information, including PII and CPNI.”[24]

Upsetting this established data privacy and security authority would particularly impair the Commission’s ability to protect American subscribers from bad actors located abroad. Foreign actor access to CPNI and PII can pose risks to the safety of sensitive customer information, to law enforcement, and to national security interests, and the Commission must retain its full privacy authorities under Section 222 to combat these threats.[25]

a. The Commission’s Privacy Authority Includes Section 201(b).

The Commission’s privacy authorities are not limited to Section 222. For many years, and as recently as 2021,[26] the Commission has cited to 201(b) as a core privacy authority. For example, the Commission drew on its 201(b) authority in two 2015 privacy-related enforcement actions[27] and in the 2014 NAL against TerraCom and YourTel.[28] Additionally, on multiple occasions Commissioner Starks has emphasized privacy and data security in the context of Commission matters grounded in the Commission’s 201(b) authority.[29]

That section 201(b) confers privacy authority on the Commission is also apparent from the Federal Trade Commission’s exercise of its analogous section 5 powers to regulate harmful commercial data practices. Section 5 of the FTC Act prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or practices,[30] including harmful data practices.[31] Section 201(b) of the Communications Act prohibits “any charge, practices, classification, or regulation that is unjust or unreasonable.”[32] As the FTC can bring enforcement actions for Section 5 violations committed by companies that are not acting in their capacity as common carriers, so too can the Federal Communications Commission use its 201(b) authority to regulate harmful data practices by carriers. Both agencies have documented this understanding of their analogous authorities in a 2016 Consumer Protection Memorandum of Understanding (CP MOU) between the Commission and the FTC, which articulates that the two agencies “will continue to work together to protect consumers from acts and practices that are deceptive, unfair, unjust and/or unreasonable.”[33] The CP MOU additionally notes that “no exercise of enforcement authority by the FTC should be taken to be a limitation on authority otherwise available to the FCC” (and vice versa), and that “[t]o the extent that existing law permits both the FCC and the FTC to address the same conduct, the agencies agree to follow [the CP MOU] to ensure that their activities efficiently protect consumers and serve the public interest.”[34] The agencies clearly (and correctly) contemplate parallel authority between Section 5 and Section 201(b).

The Commission could not have been clearer than it was in its 2014 NAL: “carriers are now on notice that in the future we fully intend to assess forfeitures for [Section 201(b) data security and consumer notification] violations.”[35]

b. The Commission’s CPNI Authority Unequivocally Includes the Power to Address Both Privacy and Competition Concerns.

Regulations designed to combat anti-competitive conduct and those designed to safeguard consumer privacy are not mutually exclusive. Public Interest Advocates have highlighted the relationship between the two both within the context of the Commission’s authorities[36] and more broadly.[37] Yet some commenters have claimed that the Commission’s authority over CPNI is limited solely to competitiveness concerns.[38] This is dead wrong. From the outset, the Commission noted that “[b]ased on our reading of the 1996 Act and is legislative history, we believe that Congress sought to address both privacy and competitive concerns by enacting Section 222.”[39] Indeed, prior to 1996 there were CPNI rules specific to larger carriers, under the Computer III framework, which were focused more on preventing anticompetitive advantage than on protecting privacy.[40] The Commission noted that Congress’s intent with the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was “a specific and different balance in section 222”;[41] that “[i]n contrast to other provisions of the 1996 Act that seek primarily to [increase competition], the CPNI regulations in section 222 are largely consumer protection provisions that establish restrictions on carrier use and disclosure of personal customer information”;[42] and that Congress “enacted section 222 to prevent consumer privacy protections from being inadvertently swept away along with the prior limits on competition.”[43]

Not long after, in 2002, the Commission noted that “[t]hrough section 222, Congress recognized both that telecommunications carriers are in a unique position to collect sensitive personal information—including to whom, where and when their customers call—and that customers maintain an important privacy interest in protecting this information from disclosure and dissemination.”[44]

V. The Threat Landscape is Worse Now Than in 2016.

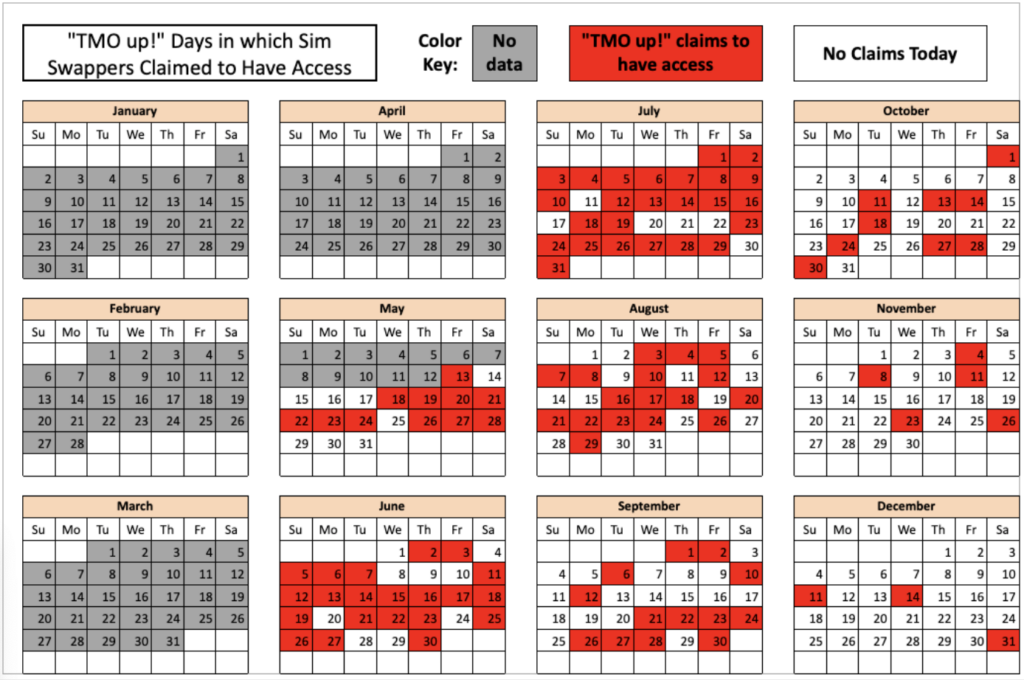

Our defenses against cyber threats cannot improve if we are in denial about just how deficient our current measures are and how these deficiencies have grown more severe over time. Nearly half of US consumers have been affected by data breaches where a company holding their personal data was hacked, compared to a global average of just 33% of consumers.[45] Even if the focus is narrowed solely to breaches of phone subscriber data that have been revealed since this docket opened two months ago, it is clear that urgent Commission action is required.[46] As one example, the red in the calendar graphic below depicts the days on which known SIM-swapping groups advertised access to T-Mobile’s employee tools (i.e., sold access to subscriber information only a carrier’s employee should have):[47]

Along with the AT&T vendor breach revealed earlier this month, the calendar above (published on February 28, 2023) represents more than 100 days in 2022 during which bad actors were buying and selling unauthorized access to phone subscriber data at T-Mobile. AT&T and T-Mobile are among the nation’s three largest carriers. (See more on the severity of the problem in Section II of EPIC’s initial comment.)[48] Several other commenters agree that the threat landscape has gotten worse.[49]

The Commission noted in 2002 that “as data mining and personalization capabilities mature, the value of personal information increases, as do the carrier’s incentive and opportunity to sell CPNI and third parties’ incentive and opportunity to purchase it.”[50] At that time, the Commission concluded that “a carrier with whom a customer has an existing business relationship has an incentive not to misuse its customer’s CPNI or it will risk losing that customer’s business.”[51] Although well intentioned at the time, this assertion has ultimately proven incorrect. As the 2020 NALs demonstrated, that incentive was not sufficient to stop carriers from looking the other way when downstream recipients of CPNI violated the terms of their contracts. And as the last two months of revealed breaches demonstrate, the Commission has not yet implemented sufficiently strong incentives for carriers to bolster data security either. The factual background now is clearly worse than it was in 2016.

VI. Commenters on TRS Issues Raise Severe, Fundamental Privacy Concerns.

We echo the concerns raised by Accessibility Advocacy and Research Organizations (AAROs) regarding privacy protections for TRS users, especially as relates to the possible exposure of the content of communications.[52] We support their proposals to presume harm in the case of a breach of TRS data[53] and to share reports with the Commission’s Disability Rights Office (DRO).[54] We strongly disagree with Hamilton Relay’s comment that “assurances of privacy” extended to TRS users are limited to CPNI.[55]

The Commission should clarify that a breach impacting TRS users requires notification to the impacted user as well as to the Commission, even if unintentional. This requirement is more than justified by the pervasive illegal disclosure of location data in the above-mentioned 2020 NALs; the proposal in this NPRM to define “breach” to account for inadvertent disclosures (not merely intentional disclosures); and the legal requirement for functionally equivalent protections for users of TRS. As it is already illegal for a communications assistant (CA) to disclose the content of any relayed conversation under 47 C.F.R. § 64.604(a)(2),[56] and generally is illegal for anyone to disclose the contents of wireless communications for personal benefit,[57] breaches of TRS transcripts constitute per se unfair or unjust practices and therefore violations of 201(b). The Commission should explicitly affirm this in this proceeding, as well as any other protections against inadvertent disclosure of the personal information of TRS users. For example, transcripts likely constitute “private or sensitive data that a customer would normally wish to protect.”[58]

As we argue above,[59] and in direct contradiction to the comments of Hamilton Relay on the matter,[60] the Commission has long established that its privacy authority extends beyond the listed factors in Section 222(h). Section 225 requires “functional equivalency” for TRS users.[61] This means that functionally identical protections—such as privacy and data security safeguards for personal information assured under Sections 222 and 201(b)—should be extended to TRS users. Because providers are in the best position to prevent the harm of inadvertent disclosures of the content of communications, the Commission should task them with notifying consumers promptly as soon as they discover they have failed in their charge. As the AAROs coalition notes in its comment: “[t]he Commission’s TRS breach notice requirements must account for the heightened harms that data breaches could have on TRS users.”[62]

Additionally, regardless of whether TRS is classified as a Title II telecommunications service, it is a “communication by wire or radio” and therefore subject to the protections of Section 705 of the Act.[63] The Commission should clarify that any publication of the contents of a TRS communication—such as transcripts—is a per se violation of Section 705. The Commission should also find that disclosure of any personally identifying information is disclosure of the “existence” of TRS communications either transmitted or received by the individual, and therefore prohibited under Section 705.

Similarly, given the unique sensitivity of the data potentially at issue in the event of a breach of TRS data, we support AARO’s suggestions that the Commission presume harm has occurred in the case of a TRS breach (although we generally disagree that there should be a harm-based threshold for data breach reporting at all). We also support the Commission’s Disability Rights Office being copied on any required data breach notification, given the DRO’s expertise in and mandate regarding TRS issues and the unique sensitivity of the data at risk.

We also urge the Commission to adopt and promote the principle of data minimization as a means of ensuring data security. The FTC and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have each recently articulated a similar approach,[64] and Commissioner Starks has suggested a data minimization model in the context of broadcaster data collection and targeted advertising.[65] We offer this suggestion not merely in the context discussed in the comments of Sorenson Communications LLC,[66] but also generally as a means of safeguarding subscriber data. Namely: if data is properly disposed of (or never collected in the first place), it cannot be misused.

VII. Consumers Must be Informed; Thresholds May Be Appropriate for Notification to the Commission.

The highest priority in this proceeding should be protecting consumers. While it is unfair to place the burden on consumers when providers fail in their charge as custodians of consumer data, the current data security reality is such that the best interim solution is to equip consumers to protect themselves from the downstream impacts of data breaches such as identity theft and account compromise. For example, the Commission should require the inclusion of mitigation information in breach notifications.[67] We also note that unauthorized access to personal information is a privacy harm, regardless of whether that personal information is used to cause financial loss, to support more sophisticated phishing attempts to facilitate identity theft, or in ways that cause other downstream consequences of the initial privacy harm. Consumers should not have to wait until these downstream harms have already occurred to learn that their privacy was violated.

We renew our call for the Commission reject a harm-based trigger for notifications to consumers.[68] Even setting aside the long history of carriers failing to protect subscriber data,[69] carriers have a strong incentive to classify any data security incidents they think they can get away with as non-harmful and only admit to harm where the reputational harm (or enforcement penalty) of an exposed cover-up would be greater. This is problematic because in the interim between the incident and the carrier’s determination that a harm threshold has been met—or the subsequent realization that a prior determination of harmlessness was incorrect—consumers could have been taking steps to protect themselves from identity theft, account compromise, and other downstream impacts resulting from the initial harm of the unauthorized access.

Because of the storied history of employee misuse of subscriber data (whether the employee(s) were paid by bad actors, were tricked by a pretexter, or had their credentials compromised), consumers should be notified in all instances of unauthorized access to their data, even in the case of an employee opening the wrong file. Commenters’ claims about the magnitude of consumer notifications that would be sent if they were required to report every time their protocols failed to safeguard their customers’ privacy is both alarming and illustrative of how grievously deficient practices are.[70] A carrier should communicate its assessment of the level of risk it thinks a given breach caused to impacted subscribers,[71] but a carrier’s duty to disclose a breach should not depend on that internal and inherently self-interested determination. Consumers should know what information was exposed so they can make their own determination as to whether the breach is a problem for them, and this alert should not be contingent upon a minimum threshold of harm or of number of impacted consumers.[72]

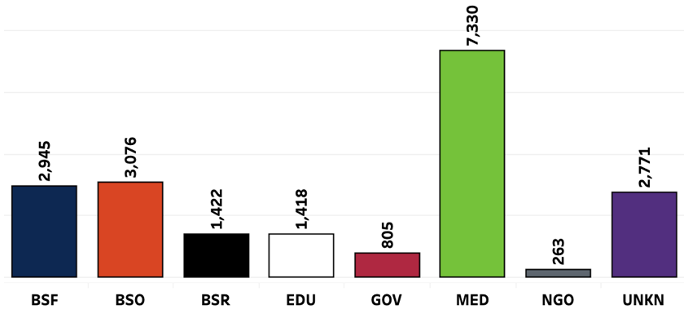

If the Commission seeks to make the security of the American phone system a priority, it needs better insight into what breaches are occurring and why. The strength of a sector’s data breach reporting regime directly impacts the quality of the information about the security of that sector. For example, Privacy Rights Clearinghouse’s Data Breach Chronology is able to publish detailed statistics on medical data breaches (see graphic below) as a direct result of the requirements of the HHS breach rule.[73] We look forward to the day that the FCC’s rules make available a similar volume and quality of telecommunications security data.

Robust notification requirements will better equip consumers to protect themselves from identity theft, including phishing attempts that use less sensitive data to obtain more sensitive data. But notification requirements will also incentivize improved carrier and vendor data security practices (including employee access controls and training) across the board, as carriers will seek to avoid the reputational harm, logistical costs, and other negative consequences of repeated breach notifications.

If despite the historical vulnerability and documented misuse of phone subscriber data the Commission still chooses to implement a harm-based trigger, at a bare minimum the Commission must establish a rebuttable presumption that harm has occurred, as it proposes in the NPRM.[74]

Because of the priority that should be given to informing consumers as quickly as possible,[75] we encourage the Commission to accept an estimated date range of when a security incident occurred rather than requiring providers to determine the precise date before sending a communication to subscribers.[76]

We still take no position on the minimum threshold for reporting a breach to the Commission or to other regulators, but we note that the GLBA’s Safeguards Rule has a proposed threshold of 1,000 impacted consumers.[77] If the Commission is to accept a minimum threshold for notification, we reiterate that it would only be appropriate in the context of reporting to regulators and in no way should obstruct timely notification to an individual consumer even if that consumer is the only one impacted by a breach.

Specific Responses to Comments by Verizon and Hamilton Relay

We note specifically that Verizon’s reference to the FTC’s ‘no one-size-fits-all’ comment about the benefits of flexibility in data security requirements is misapplied to the context of breach notifications.[78] Breach notifications are a distinct issue from the precautions the breached company should have taken to avoid notifying consumers in the first place.[79] Moreover, the need for flexibility in data security requirements (“no one-size fits-all”) does not imply the absence of a minimum threshold to ensure basic quality at all: this would be akin to arguing that because no one size fits all, we simply shouldn’t have any sizes. There is striking similarity across multiple state laws, federal sectoral laws, FTC enforcement actions, and both government and non-government frameworks regarding basic modern cybersecurity hygiene.[80] The Commission proposed in its SIM swapping and port-out fraud docket that consumers should be notified immediately of any requests for SIM changes, and that carriers should develop procedures for responding to failed authentication attempts.[81] We encourage the Commission in this docket to similarly outline its basic expectations of carriers.[82]

We also feel compelled to respond to Hamilton Relay’s claim that consumers show indifference to breach notifications, citing to a 2014 Ponemon Report. Besides the obvious age of the report, it also has been contradicted factually by several sources in the intervening nine years. Price Waterhouse Coopers and McKinsey both have since cited to the priority consumers place on privacy and data security.[83] Pew Research Center has published multiple surveys underscoring the importance of privacy and of users feeling powerless and vulnerable due to companies failing to safeguard their data.[84] In 2022, VentureBeat summarized a Thales report as indicating that “more than one-fifth of consumers stopped using a company that experienced a data breach.”[85] The Federal Trade Commission recently highlighted a 2021 study by the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, University of Michigan, and the George Washington University which found that “awareness was a crucial trigger of taking action, according to our regression results.”[86] Incidentally, this same study noted that “given that individuals may not stick with one channel to learn about breaches, breached organizations could be mandated to notify consumers in multiple channels instead of the most convenient one, and obtain confirmation from victims that the notification was received”;[87] that “breached organizations could offer victims email alias generators, password managers, or other more promising mitigation tools by partnering with respective service providers”;[88] and that “”[r]egulators should also set and frequently revisit requirements for the types of services breached organizations must offer as compensation.”[89]

VIII. The Commission Should Clarify That “Customer” Includes Anyone Who Provided Information to Establish a Customer Relationship.

In our initial comments, we urged the Commission to reiterate that data security protections apply to prospective subscribers—for example, Lifeline applicants.[90] Here, we urge the Commission to clarify that its definition of “customer” includes former customers, prospective customers, or anyone else who at any time provided information to the provider as part of the process of establishing a consumer relationship. We note that this pertains not only to privacy concerns but also to competition under Section 222(b). We reiterate that data minimization practices could assist in preventing harm here, as data cannot be newly breached after it has been properly disposed of.

IX. The Commission Should Look into Web-Enabled Vehicles as an Attack Vector, Partnering with Other Agencies as Necessary.

One commenter argues that aftermarket telematics providers and vehicle manufacturers who embed telematics should be treated as Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs).[91] We do not take a position on this issue at this time, but we acknowledge that the privacy of consumer data collected by vehicles should be protected and encourage the FCC to work with its partner agencies to identify the nature of the underlying services and how best to safeguard the associated information.

X. Conclusion

We again applaud the Commission’s attention to the increasingly severe and largely avoidable impacts of data breaches on phone subscribers, and we reiterate the importance of strengthening the overall security of America’s networks and protecting consumers from the harms of breaches.

[1] Electronic Privacy Information Center, https://epic.org/

[2] See in re Implementation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996: Petition for Rulemaking to Enhance Security and Authentication Standards For Access to Customer Proprietary Network Information, EPIC Petition, CC Docket No. 96-115 (Oct. 25, 2005), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/5513325075 [hereinafter “EPIC Petition”].

[3] See, e.g., In re Empowering Consumers Through Broadband Transparency, Comments of CDT, EPIC, and Ranking Digital Rights, CG Docket No. 22-2 (Feb. 16, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102161424008021; In re Location-Based Routing for Wireless 911 Calls, Comments of EPIC, PS Docket No. 18-64 (Feb. 16, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10216148603009; In re Rates for Interstate Inmate Calling Services, Letter Comment of EPIC, WC Docket No. 12-375 (Dec. 15, 2022) https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/121545964412.

[4] Center for Democracy and Technology, https://cdt.org/.

[5] Privacy Rights International, https://privacyrights.org/.

[6] Data Breach Chronology, Privacy Rights International, https://privacyrights.org/data-breaches.

[7] Public Knowledge, https://publicknowledge.org/.

[8] Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n, In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, WC Docket No. 22-21 at ¶ 1 (Jan. 6, 2023), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-22-102A1.pdf.

[9] See, e.g., In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Comments of ACA, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 4 n 8 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10223206458359; Comments of John Staurulakis at 3 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10223130414585; Comments of NTCA at 5 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222452510090.

[10] See, e.g., Comments of Blooston Rural Carriers at 2 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222866712777; Comments of CTIA at 27 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102222585921524; Comments of NCTA at 2 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102222921417304; Comments of Sorenson Communications at 1 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/1022263580875; Comments of Verizon at 8-9 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222240267323.

[11] See FCC Proposes Over $200M in Fines for Wireless Location Data Violations (Feb. 28, 2020), https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-proposes-over-200m-fines-wireless-location-data-violations; see, e.g., In re AT&T Inc., File No.: EB-TCD-18-00027704 at ¶ 59 (Feb. 28, 2020), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-20-26A1.pdf (“In sum, the safeguards implemented by AT&T to protect customer location information against unauthorized use relied almost entirely on contractual agreements, passed on to location-based service providers through an attenuated chain of downstream contracts”); In re Sprint Corporation, File No.: EB-TCD-18-00027700 at ¶ 18 (Feb. 28, 2020), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-20-24A1.pdf (“Sprint had broad authority under its contracts with the Aggregators to terminate access to customer location information.”); In re T-Mobile USA, Inc., File No.: EB-TCD-18-00027702 at ¶ 61 (Feb. 28, 2020), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-20-27A1.pdf (“But while that arrangement [contract between carrier and location aggregators] may have limited the number of parties with direct access to its location data, the effect of this arrangement was that the myriad location-based service providers that actually requested and used the location information of T-Mobile customers had no direct contractual relationship with T-Mobile.”); In re Verizon Communications, File No.: EB-TCD-18-00027698 at ¶ 29 (Feb. 28, 2020), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-20-25A1.pdf (“According to Verizon, it then ‘undertook a review to better understand how [the Securus and Hutcheson breaches] could occur despite the contractual, auditing, and other protections” in had in place to protect customer location data.’ ”).

[12] See, e.g., State Breach Notification Laws, National Conference of State Legislatures, https://www.ncsl.org/technology-and-communication/security-breach-notification-laws (updated Jan. 17, 2022).

[13] See EPIC Petition, supra note 2.

[14] See, e.g., Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n, In re Implementation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996: Telecommunications Carriers Use of Customer Proprietary Network Information and Other Customer Information, IP-Enabled Services, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, CC Docket No. 96-115, WC Docket No. 04-36 (Apr. 2, 2007), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-07-22A1.pdf; Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n, In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, 88 FR 3953, 3954 at ¶ 3 (Jan. 23, 2023), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/01/23/2023-00824/data-breach-reporting-requirements#p-22 (“Our current rule, adopted in response to the practice of pretexting, defines a ‘breach’ as ‘when a person, without authorization or exceeding authorization, has intentionally gained access to, used, or disclosed CPNI.’ ”) [hereinafter “NPRM”].

[15] See Rebecca R. Ruiz, F.C.C. Fines AT&T $25 Million for Privacy Breach, N.Y. Times (Apr. 8, 2015), https://archive.nytimes.com/bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/04/08/f-c-c-fines-att-25-million-for-privacy-breach/ (referring to In re AT&T Inc., File No.: EB-TCD-14-00016243 (Apr. 8, 2015), https://www.fcc.gov/document/att-pay-25m-settle-investigation-three-data-breaches); Louise Matsakis, How AT&T Insiders Were Bribed to ‘Unlock’ Millions of Phones, Wired (Aug. 7, 2019), https://www.wired.com/story/att-insiders-bribed-unlock-phones/ (referring to U.S. v. Muhammad Fahd and Ghulam Jiwani, No. CR17-0290RSL, Second Superseding Indictment (Mar. 1, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1191196/download).

[16] NPRM at 3956, ¶ 13, https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2023-00824/p-32.

[17] See, e.g., In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Comments of CCA, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 2 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/1022273286809; Comments of CTIA at 11 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102222585921524; Comments of NCTA at 3, 12-14 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102222921417304; Comments of USTelecom at 10 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/1022239177802.

[18] See in re Implementation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996: Telecommunications Carriers’ Use of Customer Proprietary Network Information, CC Docket No. 96-115; IP-Enabled Services, WC Docket No. 04-36, Report & Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 22 FCC Rcd 6927 ¶1 n.2 (rel. April 2., 2007) (“CPNI includes personally identifiable information derived from a customer’s relationship with a provider of communications services. Section 222 of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended (Communications Act, or Act), establishes a duty of every telecommunications carrier to protect the confidentiality of its customers’ CPNI. 47 U.S.C. § 222. Section 222 was added to the Communications Act by the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Telecommunications Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-104, 110 Stat. 56 (codified at 47 U.S.C. §§ 151 et seq.).”).

[19] See in re TerraCom Inc. and YourTel America, Inc., Notice of Apparent Liability for Forfeiture, File No.: EB-TCD-13-00009175 (Oct. 24, 2014), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-14-173A1_Rcd.pdf [hereinafter “2014 NAL”].

[20] 47 U.S.C. § 201(b). The Commission has further authority to order carriers to protect personally identifying information pursuant to Section 631 (47 U.S.C. § 551 (for provision of services via cable) and 47 U.S.C. § 605 (unauthorized publication of communications)).

[21] In re Quadrant Holdings LLC, Q Link Wireless LLC, and Hello Mobile LLC, 202232170008, 2022 WL 3339390, at *7 n 25 (F.C.C. Aug. 5, 2022).

[22] See NPRM at ¶ 10, https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2023-00824/p-29. We disagree with commenters that reject this proposition. See, e.g., In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Comments of CCA, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 5 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/1022273286809; Comments of CTIA at 23 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102222585921524; Comments of ITI at 5 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222861913524; Comments of NCTA at 6 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102222921417304.

[23] In re P. Networks Corp. and Comnet (Usa) LLC, FCC22-22, 2022 WL 905270, at *72 n 459 (F.C.C. Mar. 23, 2022) (citing to In re TerraCom Inc. and YourTel America, Inc., Notice of Apparent Liability for Forfeiture, File No.: EB-TCD-13-00009175 (Oct. 24, 2014)).

[24] Id. at *37.

[25] See in Re China Unicom (Americas) Operations Ltd., FCC22-9, 2022 WL 354622, at *35–36 (F.C.C. Feb. 2, 2022) (“The Commission expressed concern in the Institution Order that CUA’s service offerings provide CUA with access to both customer PII and CPNI, and that ‘this access presents risks related to the protection of sensitive customer information and the effectiveness of U.S. law enforcement efforts’… Given the record evidence in this proceeding, we conclude that, as a provider of MVNO service, CUA has the opportunity to access CPNI, including CDRs, and that CUA may access at least some PII. This access provides opportunity to engage in activities that are harmful to the law enforcement and national security interests of the United States.”) (internal citations omitted); In re P. Networks Corp. and Comnet (Usa) LLC, 37 F.C.C. Rcd. 6368 (F.C.C. 2021) (“In addition, Pacific Networks’ and ComNet’s service offerings provide them with access to personally identifiable information (PII) and CPNI concerning their customers, and this access presents risks related to the protection of sensitive customer information and the effectiveness of U.S. law enforcement efforts.”).

[26] See in re Protecting Consumers from Sim Swap and Port-Out Fraud, 36 F.C.C. Rcd. 14120 n 66 (F.C.C. 2021) (“At the same time, we emphasize that carriers have statutory duties to protect the confidentiality of their customers’ private information and to maintain just and reasonable practices and that these statutory duties are not necessarily coterminous with our rules. See 47 U.S.C. §§ 222(a), 201(b); TerraCom, Inc., and YourTel America, Inc., Notice of Apparent Liability for Forfeiture, 29 FCC Rcd 13325 (2014). Recent breaches appear to demonstrate that current safeguards are not sufficient to protect consumers’ data.”).

[27] See in re AT&T Services, Inc., 30 F.C.C. Rcd. 2808 at ¶ 2 (F.C.C. 2015) (“The failure to reasonably secure customers’ personal information violates a carrier’s duty under Section 222 of the Communications Act, and also constitutes an unjust and unreasonable practice in violation of Section 201 of the Act.”); id. at ¶ 3 (“The Notice of Apparent Liability in TerraCom states that Section 201(b) applies to carriers’ practices for protecting customers’ PII and CPNI.”); In Re Cox Commun., Inc., 30 F.C.C. Rcd. 12302 (F.C.C. 2015) (“Privacy Laws” means Sections 47 U.S.C. §§ 201(b), 222, and 551, and 47 C.F.R §§ 64.2001-2011, insofar as they relate to the security, confidentiality, and integrity of PI and/or CPNI.)”).

[28] See 2014 NAL supra note 19.

[29] See, e.g., In re Protecting Against Natl. Sec. Threats to the Commun. Supply Chain Through Fcc Programs, 35 F.C.C. Rcd. 7821 (F.C.C. 2020) (“untrustworthy equipment that threatens our data privacy and network security cannot be managed or tolerated in any form”). See also, In re Protecting Against Natl. Sec. Threats to the Commun. Supply Chain Through Fcc Programs Huawei Designation Zte Designation, 34 F.C.C. Rcd. 11423 (F.C.C. 2019) (“…I have said many times that the untrustworthy equipment from these companies could readily serve as a ‘front door’ for Chinese intelligence gathering, at the expense of our privacy and national security.”).

[30] 15 U.S.C. § 45(a)(1) (2018).

[31] See, e.g., First Am. Complaint, FTC v. Wyndham Worldwide Corp., 799 F.3d 236 (3d Cir. 2015), https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/1023142-x120032-wyndham-worldwide-corporation (failing to maintain reasonable and appropriate data security); Complaint, FTC v. Twitter, Inc., Case No. 3:22-cv-03070 (N.D. Cal. 2022), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/2023062TwitterFiledComplaint.pdf (collecting phone numbers purportedly for security purposes but then using those phone numbers for advertising purposes); Complaint, In re Support King, LLC, FTC File No. 1923003 (Dec. 21, 2021), https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/192-3003-support-king-llc-spyfonecom-matter (licensing, marketing, and selling stalkerware app).

[32] 47 U.S.C. § 201(b).

[33] FCC-FTC Consumer Protection Memorandum of Understanding 1 (Nov. 16, 2015), https://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2015/db1116/DOC-336405A1.pdf [hereinafter “CP MOU”].

[34] CP MOU at 2.

[35] 2014 NAL at ¶ 53. In this NAL the Commission also noted that “[h]ad Congress wanted to limit the protections of subsection [222](a) to CPNI, it could have done so,” id. at ¶ 15. See also In re Advanced Methods to Target and Eliminate Unlawful Robocalls, Fourth Report and Order, CG Docket No. 17-59 at ¶ 37 (Dec. 30, 2020) (‘“Section 201(b) and 202(a) grant us broad authority to adopt rules governing just and reasonable practices of common carriers”).

[36] See, generally, Harold Feld, et al., Protecting Privacy, Promoting Competition: A Framework For Updating The Federal Communications Commission Privacy Rules For The Digital World 16-24 (2016), available at: https://publicknowledge.org/policy/protecting-privacy-promoting-competition-white-paper/.

[37] See, e.g., Competition and Privacy, https://epic.org/issues/consumer-privacy/competition-and-privacy/ (last visited Mar. 22, 2023).

[38] See, e.g., In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Comments of Lincoln Network, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 14-16, 19 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102221470523919; Comments of WTA at 1, 2, 3 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102220918703760.

[39] In re Implementation of Telecomm. Act of 1996: Telecommunications Carriers Use of Customer Proprietary Network Information and Other Customer Information, 11 FCC Rcd. No. 22 at 12,521 ¶ 15, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc2042/m1/551/.

[40] See id. at 12,529, 30 ¶ 38, 40.

[41] In re Implementation of the Telecomm. Act of 1996: Telecommunications Carriers’ Use of Customer Proprietary Network Information and Other Customer Information, Implementation of the Non-Accounting Safeguards of Sections 271 and 272 of the Communications Act of 1934, as Amended , Second Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 13 FCC Rcd. No. 12 at 8,061, 8,087 ¶ 34, (Feb. 26, 1998), https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc2363/m1/345/?q=13%20FCC%20Rcd%208061.

[42] Id. at ¶ 3.

[43] Id. at ¶ 1.

[44] In re Implementation of Telecomm. Act of 1996, 17 F.C.C. Rcd. 14860, 14862 (F.C.C. 2002) (emphasis added).

[45] See Prof. Carsten Maple, 2022 Consumer Digital Trust Index: Exploring Consumer Trust in a Digital World 9 (2022), available at https://cpl.thalesgroup.com/resources/encryption/consumer-digital-trust-index-report.

[46] See, e.g., Brian Krebs, Why You Should Opt Out of Sharing Data With Your Mobile Provider (Mar. 20, 2023), https://krebsonsecurity.com/2023/03/why-you-should-opt-out-of-sharing-data-with-your-mobile-provider/; Ionut Arghire, Millions of AT&T Customers Notified of Data Breach at Third-Party Vendor, Security Week (Mar. 10, 2023), https://www.securityweek.com/millions-of-att-customers-notified-of-data-breach-at-third-party-vendor/ (approximately 9 million subscribers impacted); @TomKemp00, Twitter (Mar. 6, 2023 10:12 PM), https://twitter.com/TomKemp00/status/1632942381380276226 (noting that account number, first name, phone number, email address, number of lines and basic devices (e.g. iPhone 7) on the account, installment agreement information, and in some instances rate plan name, past due amount, monthly payment amount, various monthly charges, and/or minutes used); Brian Krebs, Hackers Claim They Breached T-Mobile More Than 100 Times in 2022, Krebs on Security (Feb. 28, 2023), https://krebsonsecurity.com/2023/02/hackers-claim-they-breached-t-mobile-more-than-100-times-in-2022/. And in January, a database of more than 7 million records of Verizon customers was revealed to have been breached, the second breach within the last twelve months. See Verizon Customer Data for Sale on Dark Web, New Data Breach Suspected, https://thecyberexpress.com/verizon-customer-data-for-sale-on-dark-web/amp/ (last visited Mar. 23, 2023).

[47] Source: Krebs, Hackers Claim They Breached T-Mobile More Than 100 Times in 2022.

[48] See in re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Comments of EPIC at 2-7 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222069458527 (section entitled “The Commission Should Expand the Definition of Breach to Reflect Modern Reality.”).

[49] See, e.g., Comments of Hamilton Relay, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 1 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222802816908; Comments of Lincoln Network at 3 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102221470523919; Comments of WISPA at 1, 2 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222237803216.

[50] In Re Implementation of Telecomm. Act of 1996, 17 F.C.C. Rcd. 14860, 14885 (F.C.C. 2002).

[51] Id.

[52] See in re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Comments of Accessibility Advocacy and Research Organizations, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 2, 3, 6 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/document/10223571503790/1.

[53] See id. at 5.

[54] See id. at 5, 7.

[55] See in re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Comments of Hamilton Relay, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 9 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222802816908.

[56] 47 C.F.R. § 64.604(a)(2), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-47/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-64#p-64.604(a)(2). Depending on the nature of the breach, a breach may also constitute a violation of 47 C.F.R. § 64.604(b)(8)(iii)(E), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-47/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-64#p-64.604(b)(8)(iii)(E).

[57] See Fed Commc’ns Comm’n, Interception and Divulgence of Radio Communications, https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/interception-and-divulgence-radio-communications (last visited Mar. 22, 2023).

[58] Quadrant Holdings, supra note 21.

[59] See Section III, supra.

[60] See Hamilton Relay supra note 55 at 9.

[61] 47 U.S.C. § 225(a)(3).

[62] Accessibility Advocacy and Research Organizations supra note 53 at 3.

[63] 47 U.S.C. § 605.

[64] See, e.g., Fed. Trade Comm’n, In re Trade Regulation Rule on Commercial Surveillance and Data Security, 87 FR 51273, 51277 (Aug. 22, 2022), available at https://www.federalregister. gov/d/2022-17752/p-88 (“The term “data security” in this ANPR refers to breach risk mitigation, data management and retention, data minimization, and breach notification and disclosure practices.”); id. at ¶¶ 43, 46, available at https://www.federalregister. gov/d/2022-17752/p-227; Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Small Business Advisory Review Panel for Required Rulemaking on Personal Financial Data Rights: Outlines of Proposals and Alternatives Under Consideration 41 at Q88 (Oct. 27, 2022), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_data-rights-rulemaking-1033-SBREFA_outline_2022-10.pdf.

[65] See Speech, Starks Remarks on the Future of Broadcast Television 6 (Oct. 19, 2022), https://www.fcc.gov/document/starks-remarks-future-broadcast-television (“What data will broadcasters be able to collect from users, and how do they intend to use it? How can they follow the important principle of data minimization, and work to achieve their goals with a minimum of data collected, stored, and shared?”).

[66] See in re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Comments of Sorenson Communications, LLC, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 2 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/1022263580875 (“The Commission’s rules currently require VRS and IP CTS providers to retain users’ sensitive data and identity-verification documents—including copies of users’ driver licenses and passports and the last four digits of users’ Social Security Numbers—long after the TRS Administrator has examined those documents and verified that the user is eligible for TRS. This needless retention of sensitive data contravenes basic principles of data security—that companies should keep sensitive user information ‘only as long as it’s necessary’ ”) (citation omitted); id. at 7-8. We do not necessarily support the rest of the Sorenson comments. For example, we believe a breach of encrypted data should still be reported, and that the burden should be on the provider to communicate clearly to consumers about the urgency of the risk of any given breach (rather than to communicate less frequently out of fear that urgent notifications will go unheeded if more notifications are sent).

[67] See NPRM at ¶ 31, https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2023-00824/p-50.

[68] See Comments of EPIC at 8-10, supra note 48.

[69] See Sections II and V, supra.

[70] See, e.g., Comments of Blooston Rural Carriers at 2; Comments of CCA at 6; Comments of CTIA at 22-23; Comments of Sorenson Communications at 4; Comments of USTelecom at 4, 6; Comments of Verizon at 2, 4, 5.

[71] See, e.g., In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Comments of CrowdStrike, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 2-3 (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/102222078707062 (discussing alerts vs. incidents, impact vs. serious impact, and mitigation, all of which a carrier could communicate clearly in its notifications to consumers).

[72] It would be appropriate for a carrier to clearly state whether breached data was encrypted or not in its notification to consumers, however we re-iterate here that encrypted data is not necessarily safe in a breach and disagree with commenters who contend otherwise. See, e.g., Comments of Blooston Rural Carriers at 3.

[73] See Data Breach Chronology, Privacy Rights International, https://privacyrights.org/data-breaches (last visited Mar. 22, 2023).

[74] See NPRM at ¶ 9, https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2023-00824/p-28.

[75] See, e.g., In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Comments of Verizon, WC Docket No. 22-21, at 5-6 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10222240267323 (“By the time 7 business days have elapsed, it may be too late for customers to secure critical accounts and take necessary protective steps.”).

[76] See NPRM at ¶ 30, https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2023-00824/p-49.

[77] See Fed. Trade Comm’n, In re Standards for Safeguarding Consumer Information, Proposed Rule (Dec. 9, 2021), https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2021-25064/p-35.

[78] See Verizon supra note 75 at 6 (quoting the FTC as saying “[t]here’s no one-size-fits-all approach to data security, and what’s right for you depends on the nature of your business and the kind of information you collect from your customers”).

[79] Although a data security program can incorporate breach notifications. See Verizon at 4.

[80] See, e.g., Comments of EPIC to the FTC Proposed Trade Regulation Rule on Commercial Surveillance & Data Security 194-197 (Nov. 2022), https://epic.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/EPIC-FTC-commercial-surveillance-ANPRM- comments-Nov2022.pdf.

[81] See in re Protecting Consumers from Sim Swap and Port-Out Fraud, 36 F.C.C. Rcd. 14120 ¶ 22 (F.C.C. 2021).

[82] The Commission has offered guidance before in the context of small entities, noting that password protections and notifications to consumers and law enforcement limit pretexters’ ability to obtain unauthorized access to CPNI. See, e.g., Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n, Small Entity Compliance Guide: Customer Proprietary Network Information (CPNI), DA 08-1321 (June 6, 2008), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-08-1321A1.pdf.

[83] See, e.g., PwC, Consumer Intelligence Series; Protect.me (2017), available at https://www.fisglobal.com/-/media/fisglobal/worldpay/docs/insights/consumer-intelligence-series-protectme.pdf (“88% say that their willingness to share their personal data is determined by how much they trust a company, and 87% will go elsewhere if they are given reason not to trust a business.”); PwC, Are we ready for the Fourth Industrial Revolution?, https://www.pwc.com/us/en/services/consulting/library/consumer-intelligence-series/fourth-industrial-revolution.html (last visited Mar. 22, 2023) (64% of consumers want assurance of immediate notification if personal data is compromised); Venky Anant, et al, The consumer-data opportunity and the privacy imperative, McKinsey & Company (Apr. 27, 2020), https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/the-consumer-data-opportunity-and-the-privacy-imperative (noting that 12% consumers reported trusting telecom companies to protect their data as compared with 18% trusting retail companies, noting that 46% consumers reported that they trust companies that proactively report a hack or breach).

[84] See, e.g., Kenneth Olmstead and Aaron Smith, Americans’ experiences with data security, Pew Research Center (Jan. 26, 2017), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/01/26/1-americans-experiences-with-data-security/ (“In total, around seven-in-ten cellphone owners are very (27%) or somewhat (43%) confident that the companies that manufactured their cellphones can keep their personal information safe; a similar share is very (21%) or somewhat (47%) confident that the companies that provide their cellphone services will protect their information…. At a broader level, roughly half (49%) of all Americans feel their personal information is less secure than it was five years ago.”); Brook Auxier, et al, Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused, and Feeling Lack of Control Over Their Personal Information, Pew Research Center (Nov. 15, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/ americans-and-privacy-concerned-confused-and-feeling-lack-of-control-over-their-personal-information/ (“81% of Americans think the potential risks of data collection by companies about them outweigh the benefits… Roughly seven-in-ten or more say they are not too or not at all confident that companies will admit mistakes and take responsibility when they misuse or compromise data”); Andrew Perrin, Half of Americans have decided not to use a product or service because of privacy concerns, Pew Research Center (Apr. 14, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/14/half-of-americans-have-decided-not-to-use-a-product-or-service-because-of-privacy-concerns/ (“Overall, adults who experienced any of these three data breaches were more likely than those who did not to avoid products or services out of privacy concerns (57% vs. 50%).”).

[85] VB Staff, Report: 33% of global consumers are data breach victims via hacked company-held personal data, VentureBeat (Dec. 11, 2022), https://venturebeat.com/security/report-33-global-consumers-data-breach-victims-hacked-company-held-personal-data/.

[86] Peter Mayer, et al, “Now I’m a bit angry:” Individuals’ Awareness, Perception, and Responses to Data Breaches that Affected Them 12 (2021), available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_events/1582978/now_im_a_bit_angry_-_individuals_awareness_perception_and_responses_to_data.pdf.

[87] Id.

[88] Id. at 13.

[89] Id.

[90] See Comments of EPIC at 10, supra note 48.

[91] See, e.g., In re Data Breach Reporting Requirements, Comments of Privacy4Cars, WC Docket No. 22-21 (Feb. 9, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/search/search-filings/filing/10209994106253 (noting, for example, that “[w]hile deleting data stored on devices when they are refurbished or resold is a widely adopted practice in the smartphone industry to avoid inadvertently disclosing customer information to future device users, it is seldom adopted by vehicle retailers (dealerships) or wholesalers (fleets, auto finance, and insurance companies)…. Our audits show that more than 4 out of 5 vehicles are resold while still containing the personal information – typically unencrypted – of the previous owners and family members”).

Support Our Work

EPIC's work is funded by the support of individuals like you, who allow us to continue to protect privacy, open government, and democratic values in the information age.

Donate