APA Comments

In the Matter of Empowering Broadband Consumers Through Transparency

CG Docket No. 22-2 (Mar. 2022)

COMMENTS OF THE ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION CENTER

to the

FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION

Request for Comment on Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Re: Empowering Broadband Consumers Through Transparency, CG Docket No. 22-2

87 Fed. Reg. 6,827

March 9, 2022

The Federal Communications Commission (Commission, or FCC) issued a request for comments in a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) relating to empowering broadband consumers through transparency.[1] The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) files these comments in response to the Commission’s proposed templated labels, designed to help consumers make well-informed decisions about which broadband service provider they choose to use.[2]

EPIC is a public interest research center in Washington, D.C. EPIC was established in 1994 to focus public attention on emerging privacy and related human rights issues, and to protect privacy, the First Amendment, and constitutional values. EPIC routinely files amicus briefs in consumer privacy cases and participates in rulemakings and policy discussions around broadband privacy. EPIC advocates for rules that protect consumers from exploitative data practices.[3]

EPIC appreciates the Commission’s effort to improve transparency for consumers of broadband services but urges the FCC to require broadband providers to provide clear and comprehensible disclosures that will actually inform customers about their data practices.[4] Lengthy and complex privacy policies are not an effective way to inform consumers about data collection practices.[5] The Commission must demand better from providers.

The purpose of the broadband “nutrition label” template should be to ensure that consumers are given information about a provider’s data collection, data disclosure to third parties, and data retention practices so that they can easily understand and compare services. The overwhelming majority of American consumers are concerned about companies collecting and disclosing their personal data to others.[6] The Commission’s nutrition label rule should encourage providers to limit collection of data about their customers to only what is essential for the provision of broadband services. And it should be clear from the labels whether one provider is more protective of their customers’ privacy than another. Nutrition labels that cannot be understood or used effectively by consumers without clicking through and reading lengthy legal policies are counterproductive.

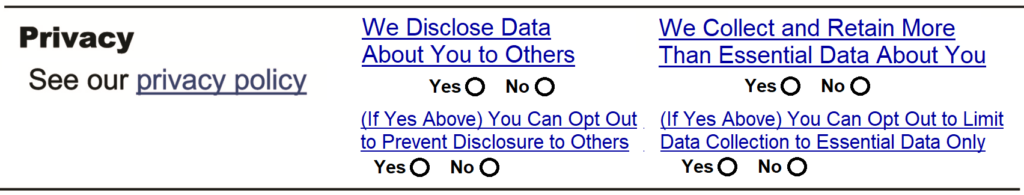

EPIC proposes that the Commission add two primary checkboxes to the nutrition label, indicating whether: (1) the provider discloses data about an identifiable user, device, or account to third parties, and (2) the provider collects any information about the consumer that is not essential to provide the consumer with broadband service (“non-essential data”). The label should also indicate whether consumers can opt out of each of the two data practices, and link to directions for opting out. These clear disclosures within the nutrition label should be supplemented by links to easy-to-understand, relevant information regarding the provider’s privacy practices, not exhaustive, multi-page legalese.

The Commission should also prohibit pay-for-privacy pricing models, which make privacy a luxury only some consumers can afford.

EPIC offers direct responses to the Commission’s questions in ¶¶ 15 and 31 regarding the scope of the labels requirement and accuracy and enforcement concerns. In short:

- The label requirement should apply to all plans for which there are active users;

- The Commission should create a new complaint category to facilitate consumer feedback on its labels, as well as a repository of current and historical plan labels;

- The Commission should impose forfeitures for misleading labels proportionate to the number of days between the misleading publication and corrective notification, as well as to the number of users in the misrepresented plan; and

- State attorneys general and other regulators should not be precluded from investigating and bringing enforcement actions where there are alleged discrepancies between the provider’s labels and its actual offerings and practices.

EPIC also emphasizes that transparency alone will not ensure privacy for all consumers if there are consumers who do not have actual, actionable choice of broadband providers.

I. The Commission Should Require Broadband Providers to Highlight Data Collection, Data Retention, and Data Disclosure in the Privacy Section of the Nutrition Label

Transparency regarding providers’ data collection, data retention, and data disclosure practices is an important component of consumer choice, as polling and pending legislation demonstrate. But privacy policies on their own are notoriously ineffective at informing consumers. As such, the Commission should require providers to report clearly in the nutrition label whether they disclose data to third parties at a more granular level than statistical (e.g., individual-level, account-level, device-level, etc.), whether providers collect and retain data about consumers that is not essential to provide the consumer with broadband service (“non-essential data”), and whether customers can opt out of each data practice.

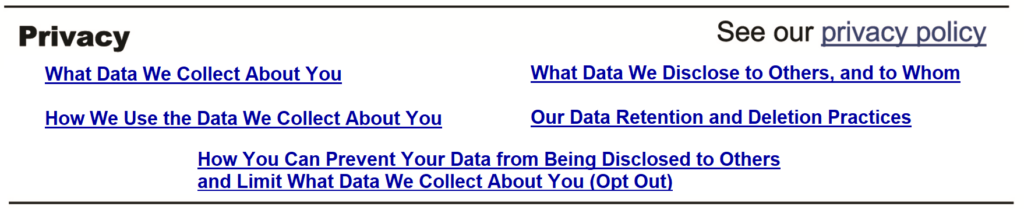

In addition, to ensure easy consumer comparison, the Commission should require that providers report their privacy policies and opt-out procedures in a standard format and link from the nutrition label to relevant resources with detailed information. The Commission’s rule should require a broadband provider to state clearly (i.e. in lay terms, not buried in an exhaustive legal document), either on a linked webpage or in the nutrition label itself: 1) what data that provider collects about its customers, 2) how that provider uses consumer data, 3) what data the provider discloses and to whom, 4) what that provider’s data retention and deletion practices are, and 5) how a consumer can opt out of disclosure of data and collection of non-essential data.

The public is deeply concerned about the risks of data collection and abuse, as recent studies demonstrate. A 2019 study by Pew Research Center found that 81% of the public believe that the risks of data collection by companies outweigh the benefits and that 79% are not confident that companies will admit mistakes and take responsibility if they misuse personal data.[7] In another Pew study from 2020, more than half of U.S. adults said they decided not to use a product or service because they were worried how much of their personal information would be collected.[8] A Morning Consult poll from 2019 found that 65% of voters felt that privacy was “one of the biggest issues our society faces.”[9] A similar poll in 2021 found that 83% of voters (86% of Democrats, 81% of Republicans) felt that Congress should make privacy an important or top priority, with 77% of voters stating that it was somewhat or very important that a privacy bill protect internet browsing history, and 81% stating the same about protecting geolocation data.[10] These are understandable concerns given prior abuses of personal data by broadband providers—for example, Verizon’s expansion of its ad program by using X-UIDH to bypass user privacy controls,[11] and the Federal Trade Commission’s recent 6(b) study of Internet Service Providers (ISPs), which uncovered providers disclosing consumer Internet traffic and real-time location data, with no meaningful choice to consumers about how their data can be used.[12] Earlier this year, Rep. Anna Eshoo, Rep. Jan Schakowsky, and Sen. Cory Booker introduced the Ban Surveillance Advertising Act aimed at stopping exploitative data collection practices.[13] Given mounting public attention to privacy, it is vital to present information about each broadband service provider’s practices regarding data collection and retention, as well as disclosure of data to third parties, and opt-out mechanisms, in a manner more transparent and accessible than a mere link to the provider’s privacy policy.

Privacy policies are notoriously vague and confusing.[14] Moreover, a company’s privacy policy may be too broad in scope to adequately inform the consumer about the collection, retention, and disclosure of data in connection with the specific service(s) that consumer is using.[15]

EPIC holds that the most effective policy for protecting consumer privacy is to prohibit secondary use and third-party disclosure of personal consumer data altogether, with narrow exceptions,[16] and to limit collection and retention of personal consumer data to only what is strictly necessary for a product or service to function.[17] But because this rulemaking is narrowly focused on how to improve transparency to consumers about current broadband provider privacy practices, EPIC proposes that the Commission’s broadband labels should provide consumers with accurate, easily-accessible, and easily-understandable information about (1) whether the provider discloses non-statistical data about consumers to third parties and how the consumer can opt out of those disclosures, and (2) whether the provider collects and retains consumer data (e.g., what websites the consumer visits) for purposes other than essential operational functions (e.g., billing[18] or customer support, but not marketing) and how the consumer can request deletion and prevent further collection of that non-essential data. EPIC suggests two simple primary Yes/No checkboxes as a means of balancing conciseness, intelligibility, and transparency.

An individual’s right to find out what information is being collected about them and how that information is used, and to prevent information collected for one purpose to be used for a different purpose (without that individual’s consent), are among the foundational principles underlying the Code of Fair Information Practices.[19] The White House’s Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights built upon these principles, providing that consumers have the right: “to exercise control over what personal data companies collect from them and how they use it”, “to [access] easily understandable and accessible information about privacy and security practices”, “to expect that companies will collect, use, and disclose personal data in ways that are consistent with the context in which consumers provide the data”, and “to [impose] reasonable limits on the personal data that companies collect and retain.”[20] As Chair Rosenworcel noted in 2016: “nine out of ten Americans believe that it is important to control what information is collected about themselves and an even greater number believe it is important to be in control of who can get that information.”[21]

Although by no means perfect, Apple has taken steps in this direction with its own privacy nutrition labels for applications in its App Store, launched in 2020.[22] These labels require app developers to disclose the types of data that their products in Apple’s App Store collect and whether that information (1) is used to track the user across devices (and is therefore disclosed to multiple parties); (2) is connected to the user’s account but not disclosed externally; and (3) is aggregated and not connected to the user’s account.[23] This framework is a helpful way of conceptualizing data collection and data dissemination, but it has its flaws. For example, the language in Apple’s model is not always clear enough. As one researcher observed, it’s unlikely that a consumer will understand what is meant by “data linked to me” and “data not linked to me.”[24] Succinct language doesn’t necessarily mean easy-to-understand language.

Recognizing the Commission’s tripartite goals of transparency, accuracy, and conciseness, it would not be appropriate to require the same level of detail in broadband nutrition labels that Apple required in its App Store. Instead, we encourage the Commission to require a short but intelligible statement about data disclosure and about data collection and retention practices. For example, a Yes/No checkbox could indicate whether the provider discloses data to third parties (where that data is more granular than statistical data)[25], and a second checkbox could indicate whether the provider collects data about its consumers beyond what is essential for the provision of broadband services to the consumer. These two primary checkboxes should each be supplemented by checkboxes that indicate whether the provider allows customers to opt out of these data practices. The primary checkboxes could be presented to consumers using succinct and easy-to-understand terminology such as “we disclose data about you to others” and “we collect and retain more than essential data about you.” The checkbox label should link to information specific to that topic. For example, the link corresponding with “we disclose data about you to others” should point to easy-to-understand information detailing what data the provider discloses and to whom, including wholly external entities as well as sister services within the same parent company.[26] The corresponding opt-out checkbox in the label should link to how the consumer can easily end further disclosure. The link corresponding with “we collect and retain more than essential data about you” should point to a brief description of what data the provider collects, how the provider may use that data, as well as the provider’s data retention and deletion policy. The corresponding opt-out checkbox in the label should link to how the consumer can easily end further collection and request deletion. These Yes/No checkboxes and links would be in addition to the currently-proposed link to the provider’s entire privacy policy. Find a rough mock-up of what this could look like below, immediately following the Privacy section of the nutrition label as proposed in the NPRM.

Privacy section, as proposed in NPRM:

EPIC’s recommended revision of the Privacy section:

Requiring checkboxes in the label, with links to tightly relevant descriptions, strikes an appropriate balance between providing consumers with meaningful information and keeping the labels brief.

If the Commission is unwilling to require providers to display and utilize these two checkboxes with corresponding opt-out checkboxes, EPIC encourages the Commission to break the privacy section of its label into five individual sub-sections: 1) data collection practices, 2) data usage practices (not including disclosure), 3) disclosure to third parties, 4) data retention and deletion practices, and 5) consumer opt-out procedures.[27] Rather than merely linking to a privacy policy in its daunting entirety, providers would also be required to link to five, separate, more digestible statements that clarify what consumers should expect when purchasing broadband access from that provider. A mock-up of what this alternative could look like is provided below.

Alternative revised Privacy section:

The Commission’s rule should make it easier for consumers to find and understand information specific[28] to the plan the broadband nutrition label describes. In the privacy section of each broadband nutrition label—either directly or via linked resources—broadband providers should convey clearly and simply their data collection, usage, disclosure, retention, and opt-out practices.[29] Communicating this kind of information to consumers in an explicit, straightforward, and standardized manner is a well-established practice in other industries, for example consumer financial information.[30] This kind of rule would be an improvement over a bare link to the entirety of the provider’s privacy policy.

II. The Labels Requirement Should Apply to All Active Plans (¶ 15)

In ¶ 15 of the NPRM, the Commission “seek[s] comment on the scope of broadband service plans to which the labels requirement should apply. For example, how should providers treat plans that are not currently available for purchase by consumers, such as legacy or grandfathered plans?”

The Commission should require a nutrition label for any plan with active users, even if it is a legacy plan, because (1) otherwise a consumer considering a new purchase cannot readily compare their current plan with prospective plans, and (2) the business practices that a consumer is currently subjected to are relevant privacy considerations, even outside the context of purchasing a new plan.

Consumers in legacy plans have an interest in accessing easy-to-understand information about the privacy practices of their current plan. Consumers should be able to easily discover and understand how their provider is collecting, using, and disclosing data about them, and what options a consumer can pursue for limiting these practices.

Additionally, if the Commission requires transparency about data collection and/or data disclosure for new plans only, this selective transparency could be misused to lure consumers away from grandfathered plans.

All consumers should be equipped to make informed choices about the technology that they may use—not merely consumers making new purchases. We urge the Commission to ensure that no consumers are left out from its worthy effort to bring transparency and competition to broadband service providers.

III. The Commission Should Implement Procedures to Verify Label Accuracy, Impose Forfeiture Penalties, and Should Not Preclude State AG’s from Taking Action Against Violators (¶ 31)

In ¶ 31 of the NPRM, the Commission seeks comment on

[H]ow to evaluate and enforce the accuracy of the information presented in the broadband consumer labels. How can the Commission verify the accuracy of the information that a broadband provider uses in a broadband consumer label? How best can the Commission confirm that any variance between the disclosed performance metrics and actual performance as experienced by individual consumers is or is not consistent with normal network variation? How should the Commission enforce against inaccuracies in the provided information?

EPIC recommends that the Commission create a new consumer complaint category, to make it easier both for consumers to provide feedback on broadband nutrition labels, and for the Commission and broadband providers to monitor and incorporate that feedback. EPIC also recommends that the Commission create a repository to house current plan labels, with an archive to store historical plan labels, to promote accountability and competition. The Commission should impose forfeitures on broadband providers who publish misleading or inaccurate broadband nutrition labels—these forfeitures should be proportionate to how long the violative label was in use and proportionate to how many consumers were using the plan misrepresented by the label, to encourage prompt corrections of deficient labels. The Commission should also make it clear that it does not intend to preclude other regulators, such as state attorneys general (AGs), from investigating allegations of misleading or inaccurate broadband nutrition labels nor from pursuing enforcement actions against broadband providers who publish misleading or inaccurate labels.

A. The Commission Should Implement Procedures to Verify Label Accuracy, Including Consumer Complaint Data and a Repository of Current and Historical Plan Labels

The Commission should create a new category of consumer complaint, related to the broadband nutrition labels, to facilitate consumer feedback on how the Commission and broadband providers might improve upon the labels. Assuming the nutrition labels will be in use for some time, this kind of iterative, democratic process can help to streamline label design and layout, make the content more consumer-friendly, and strengthen trust between consumers and providers.

The Commission should add the data value “Broadband Nutrition Label” to the data field “Issue”, making it easier for the Commission and broadband providers to identify possible improvements to labels by querying consumer complaints with this Issue value. The Issue field does not currently have a value that would readily support this kind of process. Currently, “Issue” contains values such as “Billing”, “Privacy”, and “Speed”,[31] however complaints under these categories could also stem from problems unrelated to nutrition labels. While some consumers may still select these values rather than “Broadband Nutrition Label”, providing the Broadband Nutrition Label option will improve the visibility of consumer feedback regarding the labels. To further improve consumer complaint data quality, the Commission could provide a webform for consumer complaints specific to the broadband nutrition labels with “Broadband Nutrition Label” pre-filled as the Issue value (as the Commission’s complaint webform for phone problems limits selectable Issue values to values relevant to a phone-related consumer problem[32]). The FCC could promote consumer use of this complaint webform on the webpage linked to in the footer of the nutrition label.

The Commission could also create an online repository where broadband providers are required to upload the most current version of their plan labels, with an archive that houses previous labels. This would promote accountability and transparency, and would be a de minimis burden to providers, as they are already furnishing identical information to consumers. While there would be a minimal infrastructure cost to the Commission in creating and maintaining this repository, it would be offset by the speed and ease with which investigations could be conducted into the accuracy of the information provided in the nutrition labels, and into the timeline of what information was provided to consumers when (see recommendations on proportionate forfeiture immediately below). The infrastructure cost would also be offset by the convenience to consumers who want to compare plans side-by-side based on the Commission’s labels.

B. The Commission Should Impose Forfeiture Penalties for Inaccurate or Misleading Plan Labels

The penalties for inaccuracies must be strong enough to incentivize compliance with the rules. The Commission should impose a forfeiture proportionate to both (1) the number of days the misleading information was disseminated to consumers prior to the corrective notice and (2) the number of consumers who purchased the plan or remained on the plan during the time period in which the misleading information about the plan was published. This forfeiture should apply regardless of whether the misrepresentation was intentional or inadvertent. Such an approach will encourage providers to craft easy-to-understand language in the information they provided via the Commission’s nutrition label as well as to promptly correct any misleading statements they discover in their labels. Separate forfeitures should be issued if a single offending provider has multiple plans containing misleading label information. This forfeiture should be independent of any redress sought by consumers or on behalf of consumers by other regulators, such as state attorneys general (AGs).

C. The Commission Should Not Preclude State AG’s and Other Regulators from Taking Action Against Violators

Identifying and redressing discrepancies between what a provider publishes in a nutrition label and the reality of its offerings should not be a task left to the Commission alone. The Commission should be explicit that its authority does not preclude state AGs and other regulators from investigating whether such discrepancies exist and (if so) from bringing enforcement actions against providers for deceptive or unfair practices and other state law violations, just as the AGs would for any other misleading promotional material a company presents to consumers.

IV. The Commission Should Prohibit Pay-For-Privacy Business Models

EPIC also urges the Commission to prohibit discounted pricing for consumers who are willing to permit the broadband provider to disclose their information to third parties and to prohibit providers from imposing a higher rate on users who choose to opt out of data disclosure. Similarly, a consumer’s data collection preferences should not impact what rate the provider charges them. These kinds of pay-for-privacy schemes undermine voluntary consent,[33] exacerbate existing inequities,[34] and pose additional risks to minors,[35] even where the Federal Trade Commission has COPPA enforcement authority (e.g., smart toys).[36]

V. Privacy Labels Alone Will Not Protect the Privacy of the Millions of Americans Who Lack Actual, Actionable Choice of Broadband Provider

Notice and transparency requirements only impact competition when a consumer has an actual choice of providers. Where broadband providers operate with near-monopolies, information about better alternatives is unlikely to foster competition or innovation as consumers’ desired alternatives are not realistically available to them. By one estimate, more than 83 million Americans can only access broadband through a single provider.[37] Even if these broadband labels provide perfect transparency, the Commission will not have achieved its other goals such as innovation, low prices, and high quality service if consumers do not have an actual choice amongst providers.[38] EPIC does not propose a solution to this challenge in this filing, and recognizes that the Commission is taking steps to address this issue,[39] but urges the FCC to continue to take actions in other rulemakings to address these other serious harms to consumers.

VI. Conclusion

Transparency regarding personal data collection, retention, and disclosure should be a priority for broadband providers, and EPIC applauds the Commission’s efforts in this rulemaking to provide guidance to broadband providers as to how to achieve greater transparency about their privacy practices. The Commission can further improve the proposed rule by requiring broadband providers to clearly and explicitly communicate what data they are collecting, retaining, and disclosing, as well as how easily consumers can opt out of non-statistical data disclosure to third parties and opt out of the collection and retention of non-essential data by the providers themselves. Additionally, the Commission should prohibit pay-for-privacy schemes, which exacerbate existing privacy inequities. The Commission should implement procedures to help verify label accuracy, and to easily leverage consumer feedback to improve the content and layout of broadband nutrition labels. Regarding enforcement, the Commission should impose proportionate forfeitures where providers violate its rules and should state explicitly that the FCC does not intend to preclude other regulators from bringing actions against providers who fail to promptly correct misleading or inaccurate statements in broadband plan labels.

[1] See Federal Communications Commission, Re: Empowering Broadband Consumers Through Transparency, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, CG Docket No. 22-2, 87 Fed. Reg. 6,827 (Jan. 27, 2022), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-22-7A1.pdf [hereinafter NPRM].

[2] See Federal Communications Commission, Broadband Consumer Labels, https://www.fcc.gov/broadbandlabels (last visited Mar. 9, 2022).

[3] See, e.g., Br. of Amicus Curiae EPIC in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellants Urging Reversal, In Re: Facebook Internet Tracking Litigation, 956 F.3d 589 (2020) (No. 17-17486), https://epic.org/documents/in-re-facebook-inc-internet-tracking-litigation/; Br. of Amicus Curiae EPIC in Support of Appellant, In Re: Google Inc. Cookie Placement Consumer Privacy Litigation (2017) (No. 17-1480), https://epic.org/documents/in-re-google-cookie-placement-settlement/; Br. of Amicus Curiae EPIC in Support of Neither Party Urging Reversal, LinkedIn Corp. v. hiQ Labs, Inc. (2017) (No. 17-16783), https://epic.org/documents/linkedin-corp-v-hiq-labs-inc/; Comments of EPIC to the FCC, Bridging the Digital Divide, 47 CFR 54 (Jan. 27, 2020), https://epic.org/wp-content/uploads/apa/comments/EPIC_FCC_Lifeline_Jan2020.pdf; Comment of EPIC, WC Docket No. 16-306, Re: Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services (May 27, 2016), https://epic.org/wp-content/uploads/apa/comments/EPIC-FCC-Privacy-NPRM-2016.pdf; EPIC Statement to U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Data Ownership: Exploring Implications for Data Privacy Rights and Data Valuation, Oct. 23, 2019, https://epic.org/documents/data-ownership-exploring-implications-for-data-privacy-rights-and-data-valuation/; EPIC Statement to U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Comprehensive Consumer Privacy Bill, Jan. 23, 2020, https://epic.org/documents/comments-to-house-energy-commerce-committee-on-draft-privacy-legislation/; EPIC Statement to House Committee on House Administration, Big Data: Privacy Risks and Needed Reforms in the Public and Private Sectors, Feb. 16, 2022, https://epic.org/documents/hearing-on-big-data-privacy-risks-and-needed-reforms-in-the-public-and-private-sectors/.

[4] See NPRM, supra note 1.

[5] See, e.g., Neil Richards and Woodrow Hartzog, The Pathologies of Digital Consent, 96 Wash. U.L.R. 6 (2019), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6460&context=law_lawreview ; Kevin Litman-Navarro, We Read 150 Privacy Policies. They Were an Incomprehensible Disaster, N.Y. Times (2019), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/12/opinion/facebook-google-privacy-policies.html ; Rachel Coldicutt, Data protection laws are useless if most of us can’t locate the information we’re agreeing to, Independent (Apr. 25, 2018), https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/data-protection-gdpr-facebook-cambridge-analytica-legislation-a8320381.html; Daniel Solove, The Limitations of Privacy Rights at 23 (Feb. 1, 2022), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4024790 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4024790 (noting dilemma of simpler and shorter privacy notices containing less meaningful information, suggesting separate simple consumer notice and detailed transparency statement, and premising effectiveness on vigorous regulatory enforcement, among other relevant observations); Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor, The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies, 4 I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, no. 3, 543-568 (Winter 2008/2009), https://kb.osu.edu/bitstream/handle/1811/72839/ISJLP_V4N3_543.pdf?sequence=1; Joseph Turow, Americans Online Privacy: The System Is Broken, The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania (Jun. 2003), https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1411&context=asc_papers.

[6] See Chair Rosenworcel’s statement, infra at 21 (reporting that more than 90% of Americans “believe it is important to be in control of who can get [information collected about them]”).

[7] See Brooke Auxier et al., Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused and Feeling Lack of Control Over Their Personal Information, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Nov. 15, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-and-privacy-concerned-confused-and-feeling-lack-of-control-over-their-personal-information/.

[8] See Andrew Perrin, Half of Americans have decided not to use a product or service because of privacy concerns, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Apr. 15, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/14/half-of-americans-have-decided-not-to-use-a-product-or-service-because-of-privacy-concerns/.

[9] See Sam Sabin, Most Voters Say Congress Should Make Privacy Legislation a Priority Next Year, Morning Consult (Dec. 18, 2019), https://morningconsult.com/2019/12/18/most-voters-say-congress-should-make-privacy-legislation-a-priority-next-year/.

[10] See Sam Sabin, States Are Moving on Privacy Bills. Over 4 in 5 Voters Want Congress to Prioritize Protection of Online Data, Morning Consult (Apr. 27, 2021), https://morningconsult.com/2021/04/27/state-privacy-congress-priority-poll/ ; See also, Morning Consult, National Tracking Poll #210496 (Apr. 16-19, 2021), https://assets.morningconsult.com/wp-uploads/2021/04/26163900/210496_crosstabs_MC_TECH_RVs_v1_LM.pdf at 81 (77% of voters, 81% of Democrats, and 74% of Republicans surveyed felt that it somewhat or very important that a privacy bill protect internet browsing history), at 85 (81% of voters, 84% of Democrats, and 80% of Republicans felt it somewhat or very important that a privacy bill protect geolocation data).

[11] See Jacob Hoffman-Andrews, Verizon Injecting Perma-Cookies to Track Mobile Customers, Bypassing Privacy Controls, Electronic Frontier Foundation (Nov. 3, 2014), https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2014/11/verizon-x-uidh; See also Federal Communications Commission, FCC Proposes Over $200 Million in Fines Against Largest Wireless Carriers for Apparently Failing to Adequately Protect Consumer Location Data (Feb. 28, 2020), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-362754A1.pdf (proposing fines against major wireless carriers for disclosing CPNI location information without authorization to a third party).

[12] See Federal Trade Commission, FTC Staff Report Finds Many Internet Service Providers Collect Troves of Personal Data, Users Have Few Options to Restrict Use (Oct. 21, 2021), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/10/ftc-staff-report-finds-many-internet-service-providers-collect (further noting that even where providers promised not to sell consumer data some still disclosed it, that even where providers claimed consumers have choice about how their data is used some providers made it difficult to exercise those choices, and that the definition of “business purposes” varied widely among companies claiming to keep data only as long as needed for business purposes) [hereinafter FTC ISP Study].

[13] See Press Release, Eschoo, Schakowsky, Booker Introduce Bill to Ban Surveillance Advertising (Jan. 18, 2022), https://eshoo.house.gov/media/press-releases/eshoo-schakowsky-booker-introduce-bill-ban-surveillance-advertising.

[14] See Richards and Hartzog, Litman-Navarro, etc., supra note 5.

[15] See Thorin Klosowski, We Checked 250 iPhone Apps—This Is How They’re Tracking You, Wirecutter (May 6, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/blog/how-iphone-apps-track-you/ (NY Times journalist unable to discern what data was collected and disclosed by Minecraft, because it fell under Microsoft’s general privacy policy).

[16] See, e.g., Consumer Reports and EPIC, How the FTC Can Mandate Data Minimization Through a Section 5 Unfairness Rulemaking at 16 (Jan. 26, 2022), https://epic.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CR_Epic_FTCDataMinimization_012522_VF_.pdf (listing four draft privacy bills that take this approach) [hereinafter Data Minimization Whitepaper].

[17] See, e.g., AccessNow, Why we need data minimization safeguards now (and how to do it) (May 20, 2021), https://www.accessnow.org/data-minimization-guide/; Federal Trade Commission, Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change (Mar. 2012) at 29, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-report-protecting-consumer-privacy-era-rapid-change-recommendations/120326privacyreport.pdf (providing examples of how to limit data collected, and addressing retention and deletion considerations).

[18] Even the usage of consumer activity data for billing purposes can be problematic, as in the cases of throttling or paid prioritization. See, e.g., Aria Bracci and Lia Petronio, New research shows that, post net neutrality, internet providers are slowing down your streaming, News@Northeastern(Sept. 10, 2018), https://news.northeastern.edu/2018/09/10/new-research-shows-your-internet-provider-is-in-control/; Jon Brodkin, Comcast hints at plan for paid fast lanes after net neutrality repeal, Ars Technica (Nov. 27, 2017), https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2017/11/comcast-quietly-drops-promise-not-to-charge-tolls-for-internet-fast-lanes/.

[19] See The Code of Fair Information Practices, available at: https://epic.org/fair-information-practices/ (last visited Mar. 9, 2022).

[20] White House, Consumer Data Privacy in a Networked World: A Framework for

Protecting Privacy and Promoting Innovation in the Global Economy at 1 (Feb. 23, 2012), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/privacy-final.pdf.

[21] Statement of Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel, Re: Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services, WC Docket No. 16-106 at 1, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-16-39A4.pdf (citing Pew Research Center).

[22] See Jonny Evans, 13 privacy improvements Apple announced at WWDC, Computerworld (Jul 2, 2020), https://www.computerworld.com/article/3565393/13-privacy-improvements-apple-announced-at-wwdc.html.

[23] See Klosowski, supra note 15.

[24] See Brian X. Chen, What We Learned From Apple’s New Privacy Labels, N.Y. Times (Jan. 27, 2021, updated Aug. 18, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/27/technology/personaltech/apple-privacy-labels.html.

[25] It is important that the opt out is scalable and does not require the consumer to go to each third party and request the opt out individually. See Data Minimization Whitepaper, supra note 16 at 22.

[26] See, e.g., FTC ISP Study supra note 12 at 14-17.

[27] If consumers only get two points of comparison in the label itself, those should pertain to (1) disclosure to third parties, and the ability for consumers to opt out of that disclosure, and (2) whether a broadband provider collects more than essential information about consumers, and the ability for consumers to opt out of that collection as well as retention of that data. Because data usage, deletion, and retention all relate to the broadband provider’s own practices, these practices should be included under data collection rather than with disclosure to third parties.

[28] Recall the journalist’s challenge with understanding Minecraft’s data collection practices, because consumers were only provided with a generic, overarching Microsoft privacy policy. See Klosowski, supra note 15.

[29] This should include the types of data collected, what steps a customer must take in order to opt out, etc.

[30] See Securities and Exchange Commission, sample Privacy Notice form: https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2009/34-61003_modelprivacyform.pdf, informed by Regulation P of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA).

[31] Determined by Issue values publicly visible. Federal Communications Commission, CGB – Consumer Complaints Data, available at https://opendata.fcc.gov/Consumer/CGB-Consumer-Complaints-Data/3xyp-aqkj (last visited Mar. 8, 2022).

[32] See Federal Communications Commission, Consumer Inquiries and Complaint Center: Phone Complaint, https://consumercomplaints.fcc.gov/hc/en-us/requests/new?ticket_form_id=39744 (last visited Mar. 9, 2022) (a user cannot select “Indecency” or “Loud Commercials” Issue values, for instance).

[33] See Comment of EPIC, WC Docket No. 16-306, Re: Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services at 25-26 (May 27, 2016), https://epic.org/wp-content/uploads/apa/comments/EPIC-FCC-Privacy-NPRM-2016.pdf.

[34] See Samantha Floreani, Putting a price tag on privacy, SalingerPrivacy (Sept. 28, 2020), https://www.salingerprivacy.com.au/2020/09/28/paying-for-privacy/.

[35] See Stacy-Ann Elvy, Paying for Privacy and the Personal Data Economy, 117 Columbia L. R. 6 (2017), available at: https://columbialawreview.org/content/paying-for-privacy-and-the-personal-data-economy/ (“The digital dossiers that may be compiled about children from a young age may have long-term consequences once a child reaches adulthood. The ubiquitous nature of IOT toys, social networks, and various devices that minors use to access the Internet ensure that children begin leaving digital footprints much earlier than previous generations.”)

[36] COPPA may not apply. See id. at Section IV B. Even if COPPA does apply, actual practice does not always conform to guidelines. See Noah Apthorpe, Sarah Varghese, Nick Feamster, Evaluating the Contextual Integrity of Privacy Regulations: Parents’ IoT Privacy Norms Versus COPPA 10, 13-14 (2019), available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_events/1415032/privacycon2019_apthorpe_parents_iot_privacy_norms_vs_coppa.pdf; Federal Trade Commission, PrivacyCon 2019 session 1 transcript 33-34, available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_events/1415032/session1_transcript_privacycon_2019_1.pdf (having good guidelines “doesn’t mean that the actual implementations of the toys are actually meeting those expectations themselves”; “there is some sense of security here which may not line up with

the actual implantations of the toys that we’re seeing in practice”).

[37] See, e.g., Christopher Mitchell and Katie Kienbaum, Report: Most Americans Have No Real Choice in Internet Providers (Aug. 12, 2020), https://ilsr.org/report-most-americans-have-no-real-choice-in-internet-providers/.

[38] See NPRM at 1 ¶ 1 (“competition, innovation, low prices, and high-quality service”), at 25, Statement of Commissioner Geoffrey Starks (“Arming consumers with better information will also promote greater innovation, more competition, and lower prices for broadband—wins for the entire broadband ecosystem.”).

[39] See, e.g., Federal Communications Commission, FCC Adopts Rules to Give Tenants in Apartments and Office Buildings More Transparency, Competition and Choice for Broadband Service (Feb. 15, 2022), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-380316A1.pdf.

News

See All News

Support Our Work

EPIC's work is funded by the support of individuals like you, who allow us to continue to protect privacy, open government, and democratic values in the information age.

Donate